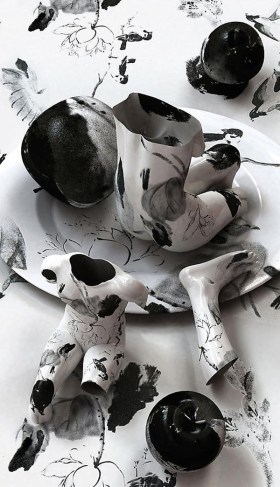

by: Lucy Gardner ((Header art by Kim Joon.))

“I imagine their bodies are hollow like the look in their eyes, lifeless forms drifting through town.” A short story that uncovers how painful it is sometimes for those who succumb to the pull of their hometown…

I was drunk and sitting in my screened porch when he called. He said he was surprised I answered after I breathed a slow “hey” into the receiver. He said it was a good day to ride and that I wouldn’t be cold. I crawled across the worn, pollen-sheathed porch on my knees like a bee in its hive. The screen-door screeched as I opened it. I could hear it down in my bones, rattling me out of a daze.

In his grandad’s garage, I stare at the walls covered in road signs we stole as teenagers. He tightens the strap under my chin, leaving the helmet’s visor open. I thought his touch would affect me more — shake my bones, raise my arm hairs, make me flinch, flame my anxiety. But his fingers are only fingers. “You still have those big lips,” he says laughing.

“Yeah, they don’t shrink,” I say.

“Still got that fiery mouth too, I see.”

My face strains not to smile. “You know, Nate loves my lips. And my nose and my cheeks and everything you used to make fun of all the time.”

He laughs and raises his eyebrows. “And where is Nate now?”

I don’t answer.

“Let’s ride,” he says, climbing on the motorcycle gracefully, his leather jacket hanging off his skinny torso. I climb on the back and hold his sides. Foreign from time, they feel wrong in my hands, a lost toy from too many Christmases ago. He revs the engine, and we roll across the concrete.

Warm air flows across my ankles and neck, igniting my senses. A frenzy of warmness within my stomach erupts in the form of a laugh. Even through the noise of the bike engine, he hears my amusement and looks in the side mirror. His eyes shimmer with satisfaction at my giddiness. We take off past the stop sign that ends his street, setting forth into the vast countryside full of pines and cows and all the shit that drops from both.

The sky is clear. We sway our bodies with the road. The road sways with us too, a black river of force. My hold on him loosens and tightens with his stops and starts. My eyes skim the fields and roads and creeks. Nature moves with us. I feel like I’m growing, being watered. We leave the road behind us a little more worn, the grasses a little more wind-blown, and the animals a little more frightened. They awaken us as we awaken them.

We reach a stop sign at an old railroad track. He stops the bike and cuts the engine.

“Bet your ass hurts, let’s take a break,” he says, removing his helmet. I move from the bike, and my ass muscles scream spasms into my legs.

“I’m fine,” I say.

“Of course you are.”

He smiles, and I recognize the small gap between his teeth. His hair flops on top where it has grown out. He still cuts the sides short to military code. He runs his hand through the flop.

“I see you finally grew your hair out. I begged you for years.”

He squats to sit on the track, legs sprawled across the rails. He chuckles and looks away. “I reckon it was time to listen to you.”

“Oh,” I say.

He lounges on the track like he’s suicidal and waiting for the end. I wait by the bike, not wanting to prolong conversation.

“So what happened with you and ole boy Nate, anyway?”

Knowing this was coming, I hold my expression still. “It just didn’t feel right anymore.”

“I see.”

He stares into the fields behind us and swats at a bug in the air. “Did you love him?” he asks.

“Yeah, of course,” I say more calmly than anticipated. “I still do.” He stands and turns to look at me. The boy I once looked at everyday looks at me again with a scruffy face and tattooed skin, evidence of our time apart.

He nods and smiles, but his eyes look weak. “You know I cared about you so much, and it was never enough.” He laughs sadly and kicks a weed up with his heel. “But I guess I shouldn’t feel so bad now. You left him too, and he has everything.”

His words burn me like vodka. I try to speak, but my throat burns.

“Alright, let’s ride,” he says, moving past me. I follow and join him, gripping his sides once again, hoping it’s enough to make up for my gagged response.

He thrusts the gas with more vigor than before, speeding away from the tracks and our homes and our town. The air is cooler now, filled with the usual March chill. Other bikers blow past us and wave salutes of camaraderie with their hands slapping the wind. One man with no helmet holds up his hands and laughs with his mouth agape, entranced in the reverie of the ride. I close my eyes. My hands hug each other around his waist. My lower-body muscles twist and tense like good sex makes them do, keeping my ass steady on the seat. My back is tense, but the pain is worth the freedom I feel cutting through the air.

We ride for miles on curves much curvier than my own. They twist us through towns with self-deprecating names: Empty Pockets, Bloody Knuckles, and Wrong Turn. Road signs that beg for us to steal, but we don’t. We leave them for the people who have nothing. We ride past double-wides and single-wides and trailers hooked to campers with tarps and tents adjacent. Little girls sit barefoot on tops of cars. Men crouch to fix their chickens’ fences, so tomorrow’s eggs will be ready for cracking. Women and children alike blow smokes on their porches; the ceilings have yellow rings where they stand. They throw their hands up in salutation and so do we. “You ready to go home?” he yells over the roar of the bike.

“No,” I say, “keep going.”

He nods and we cross into the next shanty town. The bridge takes us to the following place, and we glimpse new faces and new pains in old faces with old pains. They nod to us or simply stare. I imagine their bodies are hollow like the look in their eyes, lifeless forms drifting through town. And I imagine these peoples’ grandparents all worked together in the old mills dotted here and there, gossiping, having sex and gambling Friday’s check away in a bar on Saturday with homemade moonshine and whiskey, then walking up church steps one after the other on Sunday. Their kids grow up, having sex and naming their babies after their mamas, losing their jobs overseas, staying in place to rot together until they zombify the broken mill town. The smokestacks haunt the town square with cancerous material, warning signs, and decade-old ghost stories. Railroad tracks lead to faraway places with lighter skies and books and money and people who don’t have vacant bodies. But no one ever follows the tracks. They just stay and smoke.

As we climb the steep slopes across the town, I watch the dam below us creep over jagged river rocks. The pooled water at the top is too shallow to move over the rocks, so it sits still like glass. Only a drop or two gets out. I look into one and see myself staring, visor up.

“Sorry, I shouldn’t have brought you here,” he says with the bike idled and weighted on his right leg. “It’s kind of sad.” I see him looking at me in the reflection of the little pool below us. I nod, and we ride off.

As we move back through the town to leave, kids run across the bridge’s edge, laughing and squealing elations at the possibility of being tagged. Their feet are dirty and stained with filth; most likely strong and calloused like mine used to be. As we pass the end of the dam, a boy and a man with fishing poles and red hair examine a fish. The boy skips; the man chuckles and releases the fish into the kid’s hands. I nod as we pass.

Nate took me fishing once. We caught fourteen fish that day, one after the other. The first catch was Nate’s, the second was my own. Satisfied at my success, I showed the other fishermen my catch, and they nodded back with encouragements. Then I caught another one and another one and another one. I threw those back. I threw them all back, and we left.

We ride some more and come upon a family of six or seven piling out of an old Impala in front of a restaurant. “Kids eat free on Tuesdays” waves a sign hanging off the building’s front. Toppling out of the car and onto the gravel, blonde heads bounce and holler, moving to circle around their mother. Their missing-teeth smiles are more infectious than even the most beautiful set of pearly whites.

“We should eat here,” I say. The bike glides in and out of a pothole on the way in, and it draws the attention of the kids. They whoa and oooo at us.

“You sure you wanna eat here?”

“Sure,” I say. We disarm ourselves of our gear. My helmet catches as I try to pull it off. He moves to grab it, calmly finding the strap with his hands beneath my chin as he had earlier. This time I feel him. His eyes shine blue like the children’s had. I remember old photographs of him as a child with his mother and sisters. His head alight with blonde as well. Over time, it darkened like the rest of us.

We walk into the restaurant and find a booth. A dim lamp gloweres down on the etched names in our table. Margie & Greg ‘72 are sunk a few millimeters into the oak.

“What can I get y’all tonight?” asks the waitress. She’s got a deep rasp. I wonder how many cigarettes it took to get her voice like that. She wears blue eyeliner like my mothers in the ‘80s, and her skin looks extra thick with her dark tan. She tilts her head to the right a little and smiles. “You alright, kid?”

“Yes, ma’am,” I say with a croak. My thoughts strangle my vocal chords. “I’ll have a Coke.”

“Be right back,” she says with a wink. He must have already ordered.

“I know this isn’t what you’re used to, but I’m not the one who picked the place,” he says chuckling.

“I like this place,” I say. “Feels like home.” He pauses for a minute and stares. The waitress drops off a Coke and a Bud Light. He’s not even twenty-one.

“But you don’t like home, I thought. You said you were leaving us to rot.” The retelling of a quote of his own visibly stings. It rings from my vocal chords exactly the way it rolled off his own. I take his Bud and drink.

Lucy Gardner is a sixth grade English teacher and the 2018 winner in fiction for the South Carolina Academy of Authors.