An article which thoughtfully explores how freeing one’s mind to make room for spontaneous thought can lead to wondrous results…

by: David Raney

“All of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone.”

– Pascal

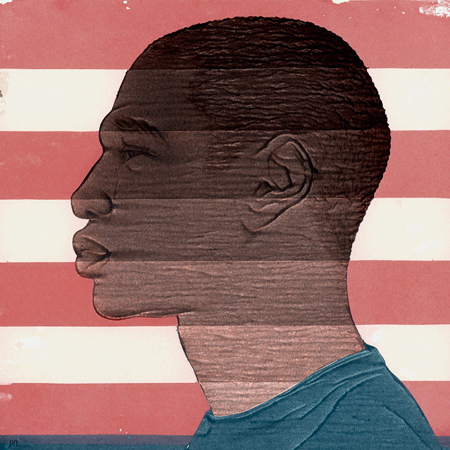

Everyone knows the virtual world has turned us all into kittens batting at a laser pointer. Or, to switch “pet”aphors, neuroscientist Erman Misirlisoy asserts that our attention is “scattered across the multiple forms of distracting media in our lives” until “we end up like dogs on a leash…dragged one way, dragged another.” My dog is approximately the size of a Volkswagen, so it’s an open question who’s being dragged. But the point stands.

Our attention span, in any case, no longer outperforms a goldfish’s. In 2000 the average stood at twelve seconds, three longer than Dory’s, but by 2015 that had dropped to eight. Desk workers in 2004 spent about three minutes looking at each screen, and ten years later it was under a minute, meaning we now switch tasks hundreds of times a day.

You may think this “continuous partial attention” measures efficiency and not scattered thinking, that we’re all master multitaskers. But researchers have known for a long time that we’re lousy at that. “Our brains simply aren’t optimized for it,” writes Jennifer Senior, “slaloming between two streams of information.” Everyday experience is clear on this — car phones cause 1.6 million wrecks a year — and so is the research. A Carnegie Mellon study found that when students are interrupted during a test their performance dips by 20%. A 2009 Stanford study of the same age group wanted to know “how today’s college students were able to multitask so much more effectively” than adults. The answer: they weren’t. “Multitasking,” the study summed up, “is not only not thinking, it impairs your ability to think.”

But we do it anyway, with smartphones, our preferred tether to the world. You’ve seen the numbers: 44% of Americans fall asleep with their phones in their hands, 35% think first about their phone in the morning not their significant other — who comes in third behind coffee — and, once awake, we check our phones 150 times a day. For over 80% of us that includes while driving, and every month Facebook records 50 million posts about lost phones, generally from other phones.

It seems a poignant irony that the word most used in passwords is “love” but more than a third of us check our phones on dinner dates, and one in five during sex (or that’s how many admit to it). Seventy years on, Orwell’s little black box looks as prescient as anything in 1984 — a rectangle that both speaks and listens and “could be dimmed, but there was no way of shutting it off completely.”

We’re paying for it, literally. Americans are exposed to an estimated 5000 ads per day, and instead of driving past billboards we’re now inviting them in for a chat. We pay for it in smarts, too. One study suggests that the constant distraction of new information reduces a person’s IQ by ten points, double the effect of smoking marijuana.

This doesn’t seem so remarkable when you reflect that while our brains were designing the digital multiverse they weren’t also designing new brains. Moore’s Law predicts a doubling of computing power every two years, but that doesn’t apply to mental equipment for the simple reason that brains aren’t computers. They weren’t hydraulic pumps in ancient Greece either, or clocks or telegraphs, however handy those analogies have been. Some shared language (circuits, network, memory) doesn’t render a metaphor real. As economist Tim Harford puts it, “We’re happy to acknowledge that we only have two hands but refuse to admit that we only have one brain.”

You don’t need to be a technophobe to wonder if it’s entirely a good thing to put half our brains in the cloud. Harford describes the first time he took to Twitter to comment on a public event, a televised 2010 prime-ministerial debate: “The sense of buzz was fun; I could watch the candidates argue and the twitterati respond, compose my own 140-character profundities and see them being shared. I felt fully engaged with everything that was happening. Yet at the end of the debate I realised, to my surprise, that I couldn’t remember anything that Brown, Cameron, and Clegg had said.”

Half a century ago Paul Theroux noticed the same thing about older technology. A friend in Kenya squeezed off dozens of photographs of giraffes, then complained he “never got a good look at them,” prompting Theroux to remark, “Taking a picture is a way of forgetting.” Travel writer Kevin Barry’s updated version: “When I think of my old trips now I think not of the great cathedrals, or the bustling alley life of the barrios, or the sweet wines, or the fried fish, or the beautiful people. I think of the internet cafes.”

We’re torn between fixing this and needing a fix. Even Tristan Harris, former product manager at Google and founder of the Center for Human Technology, says “My phone is a slot machine. I know exactly how the psychology of this works, but I still get sucked into it.” Acoustic ecologists call for true quiet, a place without all the taps and apps, flashes and crashes. But an internet cleanse is unlikely unless you plan on becoming a mountaintop guru. It isn’t going to be 1999 again any time soon. For that matter, life was already busy and loud when Proust retreated to his cork-lined room to write.

Many proposed solutions are just high-tech anti-tech, reinforcing the problem rather than solving it. Just $700, for instance, will get you “smart glasses” which keep you off your phone by darkening their lenses. Or you might prefer Coat of Silence paint, which I swear I’m not making up though it sounds like faulty recall of Get Smart, or perhaps the Pythonesque “Noise Eater Isolation Foot” or — should you have noisy neighbors — the intriguingly titled Sonic Nausea Electronic Disruption Device.

Or go retro. Novelist Jonathan Franzen decided it was impossible to write serious fiction while connected to the internet and filled his laptop’s Ethernet port with superglue. Journalist Gaia Vince tried a program that “blacked out my screen apart from the page I was working on, making my computer more like a typewriter than a box of entertainment.” The “ultimate luxury” at one Baden-Baden hotel turns out to be a silver switch by the bed that blocks wireless.

Writer Steve Lagerfeld hints at a different answer when he notes that car time “is often private time, leaving you alone with your thoughts in your own self-contained capsule. Or perhaps with the absence of any thoughts. Driving occupies one part of the mind while leaving the other parts to wander.”

Phones and iPods can intrude there too, of course, and cars aren’t key, although Elon Musk reportedly had two of his best ideas while creeping along LA freeways. Bill Gates used to remove himself from the office twice a year, not for vacations or work retreats but to do nothing. He attributes much of Microsoft’s success to ideas that cropped up during those Think Weeks.

The down in this downtime is a thing we don’t do much anymore. We tend to consider brain and body stillness as basically the same, and both a waste of time. But we ought to rethink that.

Remember being bored? Me either. Feels like it hasn’t been an option for years. But boredom isn’t stagnation. Neuroscientist Manoush Zomorodi in Bored and Brilliant calls it an “incubator lab for brilliance.” She remembers hours of it as a kid but guesses her children “have never experienced that sensation. Their minds are constantly being stimulated. Every moment is filled.” And not just teens. “All of us fill the time when we used to be bored, when our minds would just wander, with texting and to-do lists. We update Google Docs or reply to email or play Candy Crush.”

That wandering, though, is crucial to creativity, because boredom ignites a network in the brain called the default mode, which sounds like a dead zone but is actually the opposite. “Our body goes on autopilot while we’re folding laundry or walking to work,” Zomorodi says, “but our brain gets really busy. We connect disparate ideas, create personal narratives, solve problems, set goals.” In freeing our minds for spontaneous thought — which I call zoning out or, if you prefer academese, “vigilance decrement” — the default mode jumpstarts creativity.

Psychologist Sandi Mann recently updated a classic 1960s creativity test by asking subjects to list as many uses as they could think of for a simple paper cup. First, though, she gave them boring things to do. The more bored they grew, the more creative their solutions. After proposing ideas like plant pots or miniature buckets, they were told to read numbers out of a phone book. Soon they were coming up with earrings, telephones, musical instruments, and (Mann’s favorite) “a Madonna-style bra.”

When our minds wander we gain access to what Sven Birkerts calls “the fresher vision of childhood.” Birkerts remembers as a child “taking in everything in my available range — the underside of the dining room table, the odd-looking old tools in the garage drawer, the way the water made a vortex as it left the tub.” Novelist Anthony Doerr, watching his children, agrees. “Everything — a roll of tape, a telephone jack, each other’s hair — warrants investigation. Whoever says adults are better at paying attention than children is wrong, we’re too busy filtering out the world, focusing on some task or other. Our kids are the ones discovering new continents all day long.” J.R.R. Tolkien discovered one of those when, bored grading summer exams at Oxford, he turned to a blank page and wrote “In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.” Lin-Manuel Miranda was inspired to write Hamilton on the first vacation he’d taken in years, at a resort in Mexico. “The moment my brain got a moment’s rest,” he says, “Hamilton walked into it.”

Mental relaxation renders us not childish but childlike, with surprising effects. The much-discussed “flow state,” deep immersion in some task, can be productive, too, but it has its drawbacks. Intense focus is limiting, by definition. It isn’t absorbing the world so much as being absorbed. And strange as it seems, that can be another kind of distraction. We have access to millions of pieces of information every second, and as non-computers we have to choose. Think of the famous experiment, beloved of YouTube, in which people told to count basketball passes completely miss a man in a gorilla suit walking by, waving. “Before attention gets to do its job,” says neuroscientist Duje Tadin, “there’s already a lot of pruning of information.”

But the pruning doesn’t clear a path to new ideas. That requires taking some of the tension out of attention, indulging in a few slow tangents without a GPS. Think of it as less focused, more three-dimensional, like a comfortable seat in an open landscape.

Or in the bathroom. “I’ve done some research on showering,” says cognitive scientist Scott Barry Kaufman — a sentence you don’t hear all that often — and his multinational study determined that 72% of people get creative ideas in the shower. “People reported more creative inspiration in their showers than they did at work.” (I doubt that this overlaps with the 12% who check their phones in the shower.) Novelist Deborah Levy turns to water, too, when a plot line snarls: “Swimming is my only remedy. I don’t consciously think about anything while I swim. Somehow this apparent lack of attention has proved good for solving most things.”

So far as I know Einstein never publicly addressed his relationship to showers or swimming, but he once jotted down: “It was in my formative years that I gained that most empirical skill, one that would remain with me the rest of my life: simply to remain in a state of near silence and observe my surroundings.”

Fine, but who has the time, much less “near silence,” for that? Except silence and quiet aren’t the same. The longest anyone has ever spent in the world’s most silent room, an anechoic chamber at Orfield Labs in Minneapolis, is forty-five minutes. In true silence you hear only your own body, and it’s said to cause hallucinations in half an hour. Creativity happens with internal quiet — and for that, as the ads say, results may vary. You can be alone with your thoughts in a humming coffee shop or a Montana cabin. Quiet is a reduction in brain whine, a disconnection that helps foster new connections.

Those unconnected minutes, where would they come from? Jobs, houses, kids, spouses, everything takes time, and we non-gurus have to deal with the blooming buzzing confusion of that. But are we so different from the “young people” who, I’m told, spend seven and a half hours a day with media? Media mediate, it’s what the word means, moving between us and the world and promising, as sociologist Judy Wajcman says, “to save us valuable time and free us for life’s important things.” That part of new tech is old news. In 1886 the push for an eight-hour workday called for “eight hours of work, eight hours of rest, and eight hours of what we will.” I wonder what people thought they’d do with all those extra hours.

How do you use yours? In a recent American Time Use Survey, 84% of respondents reported they’d spent exactly zero minutes in the previous twenty-four hours “relaxing and thinking.” In 2014, University of Virginia psychologists asked volunteers to sit in a room and “just think” for six to fifteen minutes, or, if they preferred, to give themselves mild electric shocks. Half chose the latter. One shocked himself 190 times.

The poem “Leisure” by Welsh writer W.H. Davies ends, “A poor life this if, full of care / We have no time to stand and stare.” Davies had the time in 1911, and I think we do too. A thought experiment by David Eagleman envisions an afterlife that compiles our experiences but “reshuffled,” with all the moments that share a quality grouped together. In our three score and ten we amass what would be, without our digital leashes, two years of boredom (staring out a bus window, sitting in an airport terminal) plus a lot more that I’d put in the same bucket: five months on the toilet, eighteen months waiting in line, six weeks sitting at a red light, and — wait for it — a 200-hour shower. Isn’t there time, in the busiest of steeplechase lives, for a little creative slacking?

Wherever you travel, work or play, how often do you see someone staring into space? I do it a fair amount, and whenever I return to earth I get odd looks. “Dear God,” prays a character in A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, “let me be something every minute of every hour of my life.” If that sounds admirable but also exhausting, it’s because we mistake be for do. Flow can be useful, but so can stepping out of it now and then. Sitting on the dock of the bay. Wasting time.

David Raney is a writer and editor living north of Atlanta. His essays have appeared in many journals and have been listed in Best American Essays 2018, 2019 and 2021.

Excellent detailed article, very well-written, and very funny in places. I would say more but I have to go sit down and do nothing for a while.