by: Christine Taylor

“Her father had always told Caroline that she reminded him of her mother, but she didn’t want to be that girl — the shadow of a ghost who haunted Henry Frauer’s drunken nights.”

The reading of Henry Frauer’s will went quickly, his having little to his name when he died. Drinking, gambling, and a generally reckless life were the only legacy Frauer had to leave his surviving relatives. His wife Marguerite had died when their children were young. A viral heart condition that had attacked suddenly, moved swiftly, and consumed Marguerite, with the best parts of Henry Frauer dying with her. Afterwards, Frauer’s two elder daughters held him close to their hearts like he was a wounded bird in need of attention and pity. His youngest daughter Caroline, however, fled the nest as early as she could and scratched her way into the world. News of her father’s passing reached Caroline via a telephone call placed by a distant aunt on a chilly autumn morning. After the call, she re-filled her coffee mug, and watched as the steam escaped in wispy tendrils. Although she hadn’t seen her father in more than ten years, Caroline Montigaud decided to fly to Massachusetts from her villa in southern France to attend the funeral and estate hearing. She thought that maybe her mother would have wanted her to be there.

The funeral unfolded as Caroline had expected, with garish bouquets of ornamental flowers and swaths of lilies draped over her father’s casket. Undoubtedly, the everpresent opulence was the handiwork of her aunts and her elder sisters, who had always been seduced by her father’s outwardly romantic soul. When Caroline showed up at the funeral home wearing a starched white suit and hat, her middle-sister Deborah covered her eyes with her hands, and when she turned to march off, she tripped on a side table, sending powdery mints tumbling across the carpet. The assembled aunts said, “Amen.”

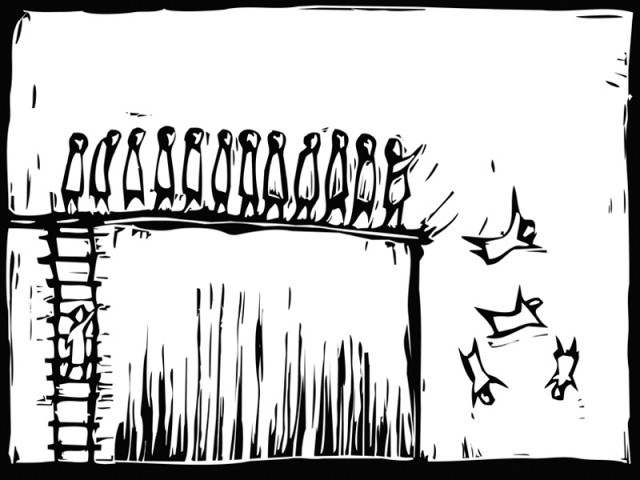

A few days after the funeral, Caroline arrived at the courthouse for the estate hearing and followed the usher to the appointed room. The aunts took up most of the front row, and Deborah and her eldest sister Adele sat just behind them, their husbands and children lined up on the benches like birds on a perch. Upon entering, Caroline took one of the seats in the back of the room closests to the room’s back the wall. Her sisters offered her cross, tight-lipped glances, and sensing the others staring, Caroline focused on reading an advertisement for a nearby restaurant that had been handed to her by a teen-aged kid had on her way into the courthouse: “Dinner made fresh on premises — just like at home.” it read. Quickly enough, the reading got underway, with pieces of her father’s estate — albeit small — gaining new ownership. When the judge read, “To my youngest daughter, Caroline Frauer-Montigaud, the locket,” Caroline looked up, puzzled. She didn’t remember seeing any family jewelry in their home while she was growing up, nor had she ever heard of any in existence. She supposed that her father would have pawned anything like that — like he did everything else — to pay for his outrageous debts. Caroline grew irritated and assumed that a horrible joke was being played on her, most likely orchestrated by her elder sisters. She had been foolish to come. Caroline wondered whether or not it was raining in France.

Saying little to her sisters or relatives and well aware of their snide remarks concerning her absence over the years, Caroline left the courthouse and headed directly to her father’s house. She would play her expected role in this charade in honor of her mother, but she wanted to get the entire trip over as soon as possible. Entering her hometown of Smallbrook, she drove past the same parks, houses, and corner stores that she had known as a child. She turned each corner without a second thought. Amazed by the ease of recollection, Caroline forced herself to think instead about the vineyards near her home in France.

At her father’s house, Caroline met the estate manager who handed her a worn, burgundy velvet-covered box and a letter. When she took the box, the locket inside rattled, and she stuffed the letter into her shoulder bag. Caroline clutched the box and walked into the backyard. Although the yard had fallen into disrepair from years of neglect, the overall look was just as she remembered it. The veranda gave way to a cobblestone patio and a small fish pond, now dry, lay on the far side of the garden. There was only one difference: the tire swing was missing. Caroline remembered begging her father to put up that swing, and thought fondly for a moment of him pushing her back and forth on summer afternoons. She recalled the joy in her mother’s laugh as she attempted to touch the sun with her toes. Now all that was gone. The old ropes, however, remained. They had warped into the great limb of the old tree and dangled freely in the wind as if reaching out to her.

Caroline abruptly turned to leave and stumbled on a garden stone, dropping the box as she steadied herself. She knelt and let the sharp gravel bury into her knees. Knelt like her father had the day her mother had lain down for her eternal nap. Picking up the box, she dusted dirt from the velvet and opened its lid. Off the shiny platinum locket glinted a dying ray of the October sun. The surface of the locket was etched with daisies, and Caroline ran her fingertip over the delicate flowers. She carefully opened the locket, stared at its face for a moment, and then snapped it shut.

She ran to her car, prepared to drive to the airport, to take the first available flight and leave Smallbrook, Massachusetts, for good. But when she reached her car, the reflection of her eyes in the rear view mirror held her attention. Those same eyes had stared out at her from the locket.

Still clutching the box, Caroline opened the locket again. The miniature black and white photo was her mirror image: the same almond-shaped eyes, high cheekbones, full lips, and straight hair. She was only six when her mother died unexpectedly, and Caroline remembered her through the eyes of a child: her comforting hand tucking Caroline in at night, her waving outside the window of the school bus, her sunny face in the backyard. Her father had always told Caroline that she reminded him of her mother, but she didn’t want to be that girl — the shadow of a ghost who haunted Henry Frauer’s drunken nights. After she moved to France, Caroline put a picture of her mother on display, an old snapshot framed in painted wood on the mantle. Yet although she tried, Caroline had never been able to see her mother’s face in her own. She couldn’t even remember her mother’s voice.

A tear fell into her lap. Caroline reached into her bag where she had put the letter. In her father’s jagged script was written, “She would have wanted you to have this, and so do I.”

Caroline folded the letter and placed it back in her bag. She took the locket out of the box and fastened the chain around her neck, holding it to her chest with her palm. She gazed out the car window at the house wondering what had happened to the time.

Christine Taylor, a multiracial English teacher and librarian, resides in her hometown Plainfield, New Jersey. She serves as a reader and contributing editor at OPEN: Journal of Arts & Letters. Her work appears in Modern Haiku, Glass: A Journal of Poetry, Menacing Hedge, and The Paterson Literary Review, among others. She can be found at www.christinetayloronline.com.