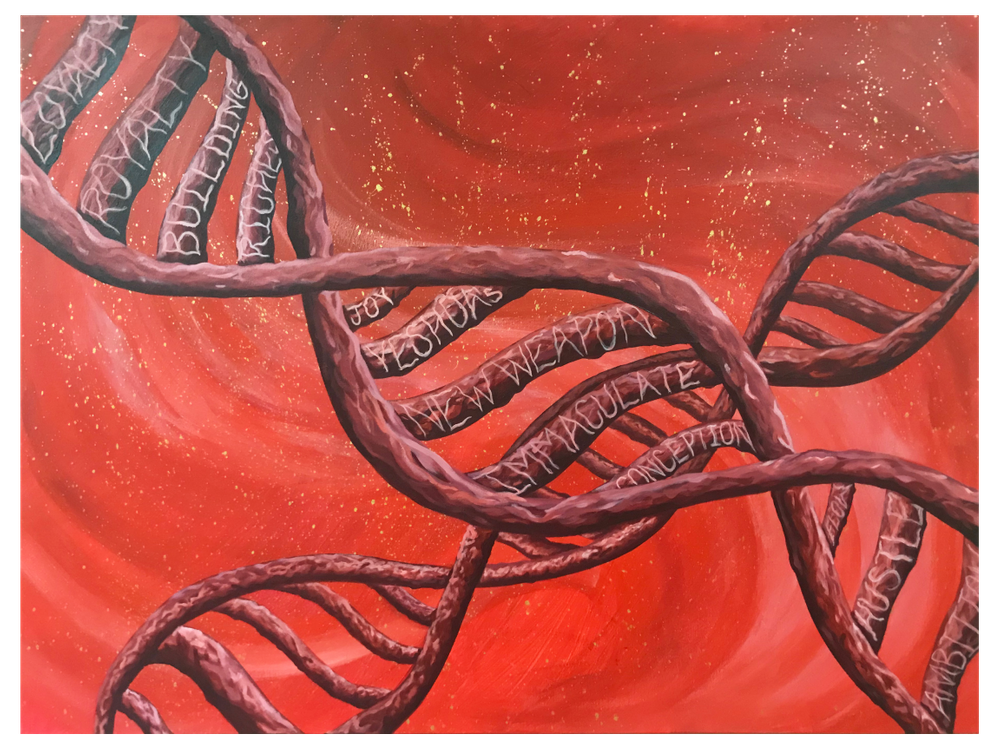

by: Jon Krampner ((Header art by Bethel-Powell.))

A surreal work of fiction where a series of supernatural events, and a considerable allotment of jealousy, threatens to consume one couple’s marriage, and lives…

The girl in the watercolor painting has golden blonde hair that rests lightly on her shoulders. Her hair is so smooth, it almost looks ironed. She’s wearing a white linen blouse with the top button open; her pink skin appears touchably soft. The powder-blue wash behind her is light and airy, like the first mild days of spring.

She appears to be in her mid-twenties, with a small, graceful nose, lips that are thin and, Fred thinks somewhat guiltily, kissable.

There’s something about the girl’s blue eyes — so bright and bordering on royal blue — that draws him in. Her eyes seem thoughtful, almost serious, and maybe a little careworn, paired with a smile hinting of a malicious gleam.

During his lunch break, Fred often wanders around the park across from the small office building near downtown Los Angeles housing the Justice Center of Southern California, the public-interest law firm where he works as a lawyer. Today is Monday, the day of the weekly craft fair. Fred talks with one of the the artists, a thin elderly woman with mottled white skin, gray curly hair, and a frank, direct gaze. She’s sitting in a deck chair at her booth, negotiating her way through a carne asada burrito.

Fred likes her paintings — a multi-ethnic panoply of Los Angeles that runs the gamut from business people to gang members, men to women, young to old. The portraits are vivid and enticing, their subjects seeming to float above the Arches White paper they’re painted on. But his eyes return to the girl in the watercolor.

“Who is she?” Fred asks.

“I don’t know,” the artist says. “I painted her aunt in Plummer Park in West Hollywood — that’s her over there,” she says, pointing to a portrait of a buxom matron. “I couldn’t quite place the accent — one of those Eastern European countries where peasants gather with torches and pitchforks to storm the hilltop castle of the expatriate Russian oligarch. She started talking about her late niece —”

“Late?” Fred asks.

“Some woman in their village accused the niece of bewitching her husband. Probably the marriage just wasn’t going well, although the lady in Plummer Park said men were drawn to her niece…”

“So what happened?”

“The lady killed her. Or had someone else do it, I don’t remember. But I felt bad for the woman so I painted her a portrait of her niece from a photo she showed me and made a copy for myself.”

“Which is this one?”

“Which is this one.”

Fred is oddly moved by the painter’s story and buys the watercolor. He takes it home and hangs it on an empty space on his living room wall opposite the sofa, next to a portrait photo taken of him and his wife Susana on their wedding day. Susana, who’s been feeling edgy since their argument last week at her 40th birthday dinner, comes home, takes one look at the girl in the watercolor and is not impressed.

“Why not?”

Susana can’t say exactly. It’s well done, but the painting unsettles her. The coloring’s wrong to Susana, the girl in the water color a blonde, a rubia, not a morena like herself. They should have picked it out together she thinks. And there’s something about her eyes. To Susana, they look like the eyes of Angelica, Fred’s equally blonde, blue-eyed colleague at the Justice Center. She has lunch with Fred more often than Susana would like and was, in fact, the subject of their argument at her birthday dinner.

When Fred and Susana met as undergrads at USC, Susana never thought of herself as the jealous type. Her parents fled Cuba with her during the Mariel boatlift and wound up in hardscrabble Downey, California, where her father Refugio worked as a handyman and her mother Catarina was a receptionist in a dentist’s office. There was never a lot of money in the house, so Susana worked hard in school and attended USC on a full scholarship. Her intelligence impressed her professors, while her emerald eyes, jet-black hair and café au lait skin impressed the male undergrads, Fred among them.

Fred, with his sandy blonde hair, blue eyes and a athletic body looks like a surfer, though he’s never had any interest in being one. He was raised in an old-growth section of Pasadena, just beyond the shadow of the Rose Bowl, where classic Greene and Greene craftsman houses are as common as corner mini-malls and street gangs in Downey. Fred had his father’s Ford dealership to thank for his comfortable upper-middle-class youth. (Bill Moard can still, to this day, be seen on late-night TV, enthusing “You’re out of your gourd if you don’t buy at Moard!”)

Despite the fact that Fred was a foot taller than Susana’s four feet eleven inches and not quite the star student she was, by senior year he had caught Susana’s eye. Because Susana had the energy of a dynamo, Fred called her his zunzuncita, the tiny Cuban hummingbird. She liked his goofy grin, deeply abiding sense of right and wrong, and the fact that he proposed to her by singing “Guantanamera” at La Cubana restaurant on Melrose Avenue in his well-intended acapella. The patrons cheered, the owner threw in a bottle of wine on the house, and Susana was so embarrassed she wanted to crawl under the table, but she accepted.

Ships leaving port with breeze-laden sails, though, can find themselves becalmed mid-journey. For twenty years, Fred and Susana had been growing older at the edge of Hancock Park. While wanting to right the world’s wrongs, Fred doesn’t always see how he’s depriving Susana of his time and attention. To her irritation, Fred rarely accompanies her to Downey. Fred likes his in-laws Refugio and Catarina — they exude a warmth he’s never felt from his own parents — but there’s always a motion to file or a deposition to review to keep him away. He promises to change, but it’s easy to get stuck in one’s habits. There was also that fling Fred had with Carol, another lawyer, at a conference in Washington, D.C., five years ago, that he guiltily confessed to Susana. He’s sure he’ll never hear the end of that one.

Their apartment is just south of Melrose, where the mean streets of Hollywood give way to the bucolic graciousness of Hancock Park. Although the address is Hancock Park, their apartment is pure Hollywood. Built during the Roaring ‘20’s by Tony Cornero, whose gambling ships evaded Prohibition by floating just beyond the three-mile limit off Santa Monica, their building is a decaying six-story brick castle. Lifelike gargoyles perch over the building’s front entrance and the once-elegant apartment features crown moldings, wainscoting, and high ceilings. Electric sconces line the hallways, which still seem dark at any hour of the day. Shadows in the Cornero Arms start to fall early in the afternoon and linger well past sunrise.

Susana decides not to press Fred about the girl in the watercolor. That night, she turns restlessly in her sleep. She wakes and looks at Fred snoring softly, then heads to the bathroom. As she washes her hands, she thinks she hears something in the living room. She takes a look around but finds nothing. The traps picked up a few mice last month, and she wonders if they’re back.

The next night, as they drift off to sleep, Susana hears a noise again, this time more distinctive — light and graceful, like a woman’s step perhaps. Standing in the darkened living room, she sees nothing, but feels someone walking past her, as if there was a cool breeze swooshing in her wake.

“Who’s there? ” she demands.

“What’s that, honey?” Fred calls from the bedroom.

Susana’s embarrassed, as if she’s been caught talking to herself.

“Nothing,” she says sheepishly. As the school psychologist at Unruh Middle School in the Mid-Wilshire District, she’s supposed to help kids with their problems, not develop her own.

Late Wednesday night, Susana edgily walks into the living room to make sure their fifth-floor windows are closed. But really she is wanting to see if anything is off. She can’t say what she is expecting. She pads around the living room. There nothing to see and nothing to hear so she returns to bed.

Twenty-four hours later as the next day as Thursday night turns into early Friday morning, Susana wakes at 3 a.m., unsettled by visions she can’t reassemble, the residue of half-remembered nightmares clinging to her like cobwebs. She gets up and walks unsteadily to the living room in her white lace nightgown and sits on the sofa, as she often does when sleepless. Susana sits in silence until the movie movie projector in her mind runs out of film and she can return to bed agreeably drowsy.

The air is cool. A police car speeds east on Melrose, its siren blaring. As it fades into the distance, silence reclaims the room. The principal is going to like my grant proposal for helping the kids cope with their electronic gadgets…Why did I get upset about Angelica? There’s probably nothing there, but Fred hasn’t been looking at me the way he used to. Susana is starting to nod off from her thoughts, and she reasons it’s time to go back to bed. That’s when she senses someone standing behind the sofa.

She rapidly wheels around, but there’s nothing there. When she turns back around, her gaze is pulled towards the wall and the watercolor stands out more clearly than it did just moments prior. It’s getting brighter, while their wedding portrait seems to fade and the room’s temperature drops. A sickly, pale light emanates from the girl in the painting.

Susana then sees the eyes of the girl in the painting moving, as if she’s trying to figure out where she is. They settle on Susana, and the look of curiosity turns into a glare of unmitigated hostility. Goosebumps rise on Susana’s arms and back. She shakes her head, closes her eyes and opens them again. But there’s no mistaking the angry look on the girl’s face.

Susana, having overcome her initial shock, glares back. It’s her home, after all. But the girl in the watercolor doesn’t back down and Susana runs to the bedroom.

“Fred! That puta is giving me the evil eye!”

Fred turns over in bed and confusedly faces her.

“Wha—?”

Susana drags him to the living room, now dark. The girl in the watercolor looks just like always.

“What’s up?” a fully-awake Fred asks with a bit of irritation. He and Angelica have to meet with LAPD lawyers in a few hours. Bob Dunn, a client of theirs, was roughed up by police officers during a routine traffic stop. Fred needs to be well-rested for the meeting.

Susana tells him what happened. Fred looks at her with suspicion. He knows she has nightmares and sometimes wakes up clinging to him. Maybe it was just a dream, he suggests. “That was no dream,” she replies, and takes the painting down from the wall.

“Who authorized you to do that?” Fred asks.

“Who authorized you to buy it without consulting me?” Susana replies while facing the painting towards the wall and they both return to bed without speaking another word.

The next day is a busy one for Susana — Fridays always are — so she runs out of the apartment without stopping to grab the girl in the watercolor and throw her in the trash. She’ll do that when she gets home.

Later on in the day she is with one of the last kids she has to talk to, Otelo, a thirteen year-old boy who was bullying a girl on the playground.

“What happened?” Susana asks.

“Filomena is my girl,” says the short, restless Mexican-American kid, puffing out his chest like a bantam rooster. “But she was talking to Jaime over by the swing set.”

“And that’s why you pushed her?”

“I had to show her who’s boss.”

“That’s not the way grown-ups settle their differences.”

“I’m not a grown-up. I’m in the seventh grade.”

“And you’ll never get to the eighth grade acting like that,” Susana says. “You made her cry.”

“I felt bad.”

“That you shoved her?”

“That she was talking to Jaime.”

At least they’re both flesh and blood, Susana thinks. What kind of santeria makes a painting come to life and start glaring at me in my own—

“Miss?” Otelo says, sensing Susana’s no longer there with him.

“Jealousy is one of the feelings that happens when you care about someone,” Susana says, returning her focus to the conversation. “But you can’t act on it like that. Are you willing to apologize to Filomena?”

“What happens if I don’t?”

“You’ll be suspended and your parents will be called in for a conference.”

More out of practicality than remorse, Susana suspects, Otelo promises to apologize. Susana clocks out and heads home.

Susana walks down the dark, fifth-floor hallway toward their apartment, the art-deco sconces barely providing enough light for her to see which key to slide into the lock.

When she closes the front door, she sees the girl in the watercolor back on the wall.

“Fred!” she calls out in her there’s-going-to-be-trouble voice.

Fred ambles into the living room from the den, where he’s been reading depositions from the Bob Dunn case.

“Hi, honey,” he says. “What’s the matter?”

“Don’t ‘Hi, honey’ me,” she says. “Why’d you hang it back up?”

“I didn’t,” he says. “It was up when I arrived home. I thought you had changed your mind.”

Susana disproves his assumption by tearing the painting off the wall, carrying it down the hallway and pitching it down the trash chute.

“That was a hundred bucks,” Fred bemoans when she returns.

“It’s cheaper than a divorce.”

Fred knows there’s no crossing Susana when she’s like this, so he acquiesces. Plus, he has a surprise for her.

“I got takeout at La Cubana,” he says.

“Arroz con pollo?” she asks.

He nods.

“With platanos maduros?” Fred nods, knowing of Susana’s weakness for the sweet fried bananas.

“You’re the best,” Susana says, and just like that, Fred is out of the doghouse. They linger over dinner, watch the 10 o’clock news and go to bed. But Susana’s insomnia returns, and in the middle of the night, she slides out of bed and returns to the living room. She sits on the sofa, glad the girl in the watercolor is no longer there.

However, she is there.

The painting is back on the wall.

The girl looks menacingly at Susana as if to say “You’ve crossed me once too often. And you’ve lost.”

It is all too much for Susana. She tries to cry out to Fred, but can’t. She starts to get up, but can’t do that, either. The surrounding air cools and a pallid light again illuminates the girl’s face. The girl’s face twists into a smirk as if to say, “He won’t believe you this time, either.”

Fred wakes up and misses Susana. He walks to the darkened living room, where she’s collapsed on the floor in front of the sofa. She looks badly frightened. Fred shakes her gently. She recoils.

“Honey, it’s me,” he says. “Wake up! You had a nightmare!”

“That was no nightmare,” she says. “Look.”

Susana points at the watercolor.

“But you threw— “

Susana nods and goes to the den, returning with a scissors and starts to take the girl in the watercolor off the wall.

“Not so fast,” Fred says. “I’ll take it back to the artist on Tuesday.”

“You’re not keeping that damn thing around here.”

“I’ll take it to my office.”

Although dubious, Susana agrees. But she locks the watercolor in their hallway closet for the night.

On Saturday morning, Fred and Susana throw some provisions in their car, then go by his office to leave the girl in the watercolor. They head up to the mountains, to the Angeles Crest. Past La Canada, the houses fall away and the scented mountain pines begin to populate the steep, dry hillsides. They drive up to Mount Waterman, find a trail Fred knows well, and hike-in a few miles to a secluded clearing. It has a good view of the surrounding peaks and, on low-smog days like this one, of the Los Angeles Basin.

Fred spreads out a blanket and pulls from his day pack caprese sandwiches, red wine and dark chocolate, what Susana calls comida clasica de gringo. Dusty sunlight filters through the pines. The cool mountain air is alive with the chirping of unseen birds. After they eat, Fred puts his arm around Susana.

“When you return the painting,” Susana says, “ask the artist if she can tell you anything more about the girl.”

Fred agrees. He’s not sure this is really a thing, but wants to do right by his wife. He asks if she wants a backrub. He tries to sound discreetly mischievous, but Susana can hear the lusty catch in his voice.

“Sure,” she says. Maybe the magic is back after all.

“Top off.”

“No way.”

“No partial nudity, no service.”

“That’s blackmail.”

“So what if it is?”

Susana’s top comes off, and then more.

“Fred,” she giggles as he starts to take his own clothes off, “someone will see.”

A light tread crackles the leaves underfoot at the edge of the clearing, and for an instant Fred has the odd feeling they are being watched. But as far as he can tell, no one is around.

Monday rolls around again and with it, the next craft fair. After taking a deposition from one of the policemen from the Bob Dunn traffic stop, Fred grabs the painting and goes to look for the woman who painted the girl in the watercolor.

To Fred’s dismay, the artist isn’t there. Her booth is occupied by Artie Cohen, a middle-aged transplant from Brooklyn, New York who does acrylic paintings of the Fairfax District.

“Where’s the woman who was here last week?” Fred asks.

The artist, irritated that Fred is neither a customer nor an admirer, shrugs.

“Do you know her?” Fred asks.

“Sure I know her. She shares her burrito with me sometimes.”

“What’s her name?”

“Helena.”

“Helena what?”

“Helena Handbasket. How should I know? Hey, Paul,” he asks the oil painter at the next booth, “Where’s Helena?”

“Oh, Jeez. I was meaning to tell you,” the young man in a Dodgers cap and Hawaiian shirt says.

“Tell me what?” Artie asks. “Kidnapped by a band of roving gypsies?”

“Helena died Saturday,” Paul says. “She made a sloppy lane change on the Hollywood Freeway.”

Fred expresses his condolences, and they talk about her for a while.

“I was hoping to learn more about her,” Fred says, holding up the girl in the watercolor.

“Helena did say something about that one,” Paul says. “The kid creeped her out. It was the only one she’d ever done where the subject’s eyes seemed to follow her around the room. She felt that way even when she had her back to the painting.”

“Looks like just another aspiring starlet to me,” Artie says.

Fred is tempted to proclaim “She comes to life when the world should be asleep and my wife is scared to death of her.” But it’s a warm day with a light breeze. What’s frightening at 4 a.m. seems silly under the mid-day sun.

“Just wanted to learn more about my new acquisition,” Fred says and walks away. He returns to his office, intending to throw the painting out. But something stops him. He knows he should get rid of it, but there’s something about the girl’s eyes, and while suppressing a feeling of guilt, he hangs the watercolor on his office wall. He doesn’t tell Susana.

Friday brings with it another birthday party, this one for Jim Greerson, a colleague of Fred’s at the Justice Center. Susana drives Fred in her 2010 silver Acura because his car is in the shop. As she pulls away from the curb, she asks the question she’s been finding reasons not to ask all week: Will Angelica be there? When Fred responds “Yes” Susana grips the steering wheel more tightly.

The party is in Studio City, south of Ventura Boulevard, where the road rises toward the eastern end of the Santa Monica Mountains and the lots and houses get bigger the higher you go. Following Fred’s directions, Susana stops in front of a sprawling ranch near the top of Laurel Canyon on the Valley side. They get out and Fred rings the bell.

“How can Jim afford this?” Susana asks.

“There’s money in his family, a lot of it” Fred says. The thought that he could have had a house like this if he’d followed his father into the car business briefly drifts through his head, then evaporates.

“Don’t say anything about the painting,” says Susana, thinking it’s in the past. “I don’t want anyone to think we’re certifiable.”

“Or that your pointless jealousy is consuming our marriage,” Fred mutters.

“What was that?”

“Just talking to myself.”

“Not as interesting as talking to Ange —“

The front door opens and Jim appears. He heartily greets them and says everyone’s in the back.

They make their way through the house — which seems as big to Susana as the auditorium at Unruh Middle School — to the backyard. It’s ringed by Washington palms, cypress, and eucalyptus trees, whose sweet, resinous aroma permeates the mild evening air. The sky is a deep cobalt at it zenith, with ever-lighter bands of blue closer to the ground resolving into a glow of bright orange backlighting rooftops to the west, where the horizon still remembers the setting sun. Lights are strung through the trees of the Greersons’ backyard, and the clink of glasses punctuates the murmur of conversations.

By 11 o’clock, Fred and Susana have wound up in separate clusters. Susana’s in a knot with one of the Justice Center lawyers, Fred’s secretary, and the out-of-town brother of the birthday boy. She looks around for Fred and sees his back at the edge of the lawn. Looking at him, deeply engaged in conversation, is Angelica.

Susana is struck by how tall and willowy she is and how gracefully she moves. She laughs at something Fred just said, holding her stomach and bending over. That must have been a good one, Susana thinks. As Angelica straightens up, she touches Fred’s elbow, her still-laughing face illuminated by the party lights strung overhead. We’ll sort this out in the car, Susana thinks.

At midnight, Susana and Fred stumble to her Acura and head south on Laurel Canyon back to Los Angeles.

“You and Angelica were having a good time,” Susana thrusts.

“It’s the Bob Dunn case,” he parries. “It’s going badly.”

“Just like things went badly with Carol in Washington?”

“The statute of limitations has expired on that one.”

“What’s Angelica got to do with the Bob Dunn case?” Susana asks.

“Have you forgotten she’s my co-counsel?”

“If the case is going so badly, what did you say to make her roar with laughter like that?”

Fred pauses, trying to remember. Susana takes his silence as an admission of guilt.

“You see?” she yells, turning to face him. “I knew all along that — “

“Look ou —“

Those are Fred and Susana’s last words. Susana had blown through the red light at Laurel Canyon and Mulholland. They might have just made it past the westbound black Hummer, but a young, blonde girl out late for a walk appears out of nowhere in front of the Hummer, causing it to swerve into Susana’s Acura. The monster of a vehicle t-bones their car, and in a fight between a Hummer and an Acura, the Hummer wins.

The Acura goes over the edge of the hillside and rolls down the hill, turning over repeatedly until it reaches the bottom of the canyon. When it comes to rest, there’s an empty, puzzled look on Fred’s face, as if he’s not quite sure how it all came to an end on the drive home from Jim Greerson’s party. Susana’s right arm is pointing at him — either she’s reaching out to embrace him, or in a gesture of j’accuse. Their car horn is stuck, its high, keening note irritating people up and down Laurel Canyon.

Several days after the funerals, Susana’s parents drive up from Downey to conduct the estate sale. A young social media director from Canoga Park who had a fight with his wife at breakfast that morning buys the girl in the watercolor. He isn’t sure if his wife will like the painting. But he can’t look away from it. There’s something about her eyes.

Jon Krampner’s short stories and flash fiction have appeared, or are about to appear, in Across the Margin, Eunoia Review, Eclipse, Page & Spine and Collective Unrest. He was selected as a finalist in the Summer 2018 Owl Canyon Press Hackathon. He lives in Los Angeles and is sarcastic in three languages.

Shades of Oscar Wilde! Nicely done.