by: Douglas Grant

An overdue introduction to the penetrating works of Sean Dietrich…..

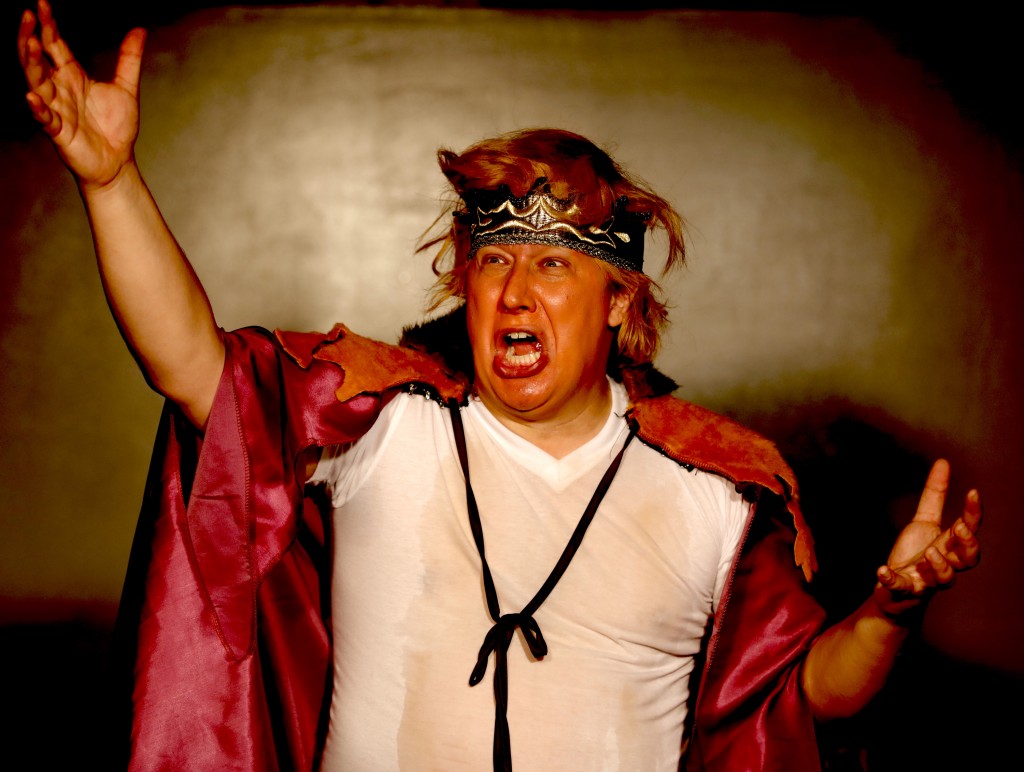

The Foxy Desert – King Tiger Girl

I first became aware of Sean Dietrich’s artwork when I was holed up in a rundown dive bar, trying to tie one on before heading to a Built to Spill show. His displayed paintings spanned the entire bar, and once I took notice of them they pretty much demanded my attention for the remainder of my time there. One of the first observations I made with regards to the subject matter of his art was a very tangible polarization of themes. There were bright eyed children standing in front of dilapidated buildings with thick black smoke stacks in the background. The sacred feminine was often present in scenes of bloody warfare. I observed portraits of fuzzy animals such as rabbits with malevolence in their eyes, and teddy bears that looked heartbreakingly despondent. I was captivated by the playful spectrum of light and dark. There was canvas after canvas of larger than life caricatures facing some of the worst crises created by humanity. I asked the bartender about the painter, but he knew very little. That bar, Landlord Jim’s, no longer exists. I wouldn’t meet Dietrich for another year. It was a chance encounter at an art show where I recognized his work and got to know him.

Dietrich began his art career at a very young age in his hometown of Baltimore. He published his first graphic novel, Tribal Scream, at the age of fifteen, and since then has gone on to pen the books Industriacide, I Brought the Gutter, Bubbles From Atlantis, and The Fruits of Our Labor. It was 2004’s publication of Industriacide that established Dietrich’s long standing relationship with independent comics publisher Rorschach Entertainment, and earned him international acclaim for his gritty and often gloomy storytelling style. The story follows three young children and a hallucination induced teddy bear as they attempt to come to face an outside world that is anything but pretty. And though it could be considered a coming of age story, it is not a story of innocence lost.

“It wasn’t about how these kids have to grow up so fast,” Dietrich explains to me. “It’s about the fact that they were so young when they were dealing with all of this.” And this statement—to me—cuts right to heart of the matter when trying to interpret some of Dietrich’s more abstract works. His paintings are full of life—life that we can sympathize with, and maybe even find humorous or cute—but these lives are very often facing the worst of human nature and the detrimental effects we’ve had on our world.

My Mind, My Castle

Early on I took notice of some recurring themes in Dietrich’s paintings. A self-admitted student of history, World War II is very prevalent in his art, both the Japanese and the German campaigns. The darker nature of the urban landscape has also been influential in his paintings. He’s called attention to our society’s love affair with fast food, and the subsequent decline in our health because of it. And he’s breathed new life into the characters of Grimm’s Fairy Tales and Aesop’s Fables, with his grainy re-imagining of these classic stories on canvas.

He’s kept tremendously busy these last few years in pursuit of his artistic endeavors. He’s recently concluded a tour with The Infusion Project, a collective of artists, musicians, fashion enthusiasts, and technological innovators that travels from city to city, holding events that are meant to stimulate creative expression and challenge one’s artistic limitations. He’s usually juggling at least three projects at all times, a process that often makes him neurotic, made more difficult by the distinction of what’s lucrative and what’s artistically rewarding.

An upcoming show in San Francisco has presented Dietrich with the unique position to encourage aspiring artists to follow through with their plans—even when faced with opposition—to enroll in academies of art and design. I was glad to hear this. I explain to him how frustrating it is for me to see the arts, music, and other humanities completely excised from the public education curricula in face of the budget crisis. Time and again I’ve seen students struggle through academia, and I wonder if perhaps it’s because they’ve had no outlet for creative expression. Unrealized talent is a travesty, and unfortunately some of our greatest prospective artists may go undiscovered as education continues to slash art courses. Dietrich agrees with me, calling attention to two of his paintings that address the same issue. His paintings Good Job California and What Were You Thinking California? depict a boy and a girl who must come to terms with the fact that the school system has essentially quelled their opportunities to pursue the arts.

What Were You Thinking California?

Social media and digital advertising are all well and good, but Dietrich’s success as an artist has stemmed from his personal interaction with his fans. During his live painting sessions in bars and night clubs, you can easily approach him and open up a dialogue. He speaks frankly and comes straight to the point. He’ll tell you about where he’s come from and where he’s headed. He’ll tell you exactly what he was thinking when he painted the canvas you just asked him about. This very personable aspect of his nature will serve him well as doors continue to open for him as he branches out into even more American cities.

I ask him why this avenue has been so successful for him. “It’s like the old days when the quacks used to set up shop right outside their wagons, selling hair tonic to the masses.” Momentarily finding this a strange comparison, I quickly realize that it’s the perfect analogy.