by: Shawn Yager (Header photograph of the Statues in Jandia taken by Tony Hisgett.)

The mirth of children, the ire of the weary, inexplicably frozen in time…

Cheyanne and Brandy walked home from school. They lived next to each other. They were the same age. They liked the same things. They even wore the same sneakers – pink and purple with silver stars. They had drawn the stars themselves.

“Jump, I dare you!” Cheyanne said to Brady.

There was a stretch along Main Street between the school and their homes where a wall held up a part of a hillside, so that the street could run straight instead of curve around it. The wall was made of stone because, here in New England, stones are what walls are made of.

Cheyanne walked along the edge of the of the retaining wall. She stood there for a moment to take in the scenery, the queen of her domain, with the gas station diagonally across from her, some shabby houses on a hill behind it, and the street itself, full of potholes. She could not see her school, an old pile of bricks, which would have been to her right. A church blocked her view of it. She turned around to face a big house with three floors, its paint peeling.

“What do they do in there, with so many rooms? Do any girls live there?”

The dark windows told her nothing.

She balanced on the edge of the wall. She had her hands out to help balance herself, like in gym class. But as she looked at the old house, she lost her balance.

“Help!”

“Oh, gosh!” Brandy said, and then laughed because she was nervous. It sounded like a horn blast.

“Not funny!”

“Sorry!”

The wall was shorter at either end. At its highest point, where Cheyanne lost her balance, the wall was about six feet tall. Unlike gym class, there was no soft mat on which to fall.

She regained her balance, stepped away from the edge, and ran the rest of the way to the end of the wall. Here it was only about a foot high. She laughed, another horn blast.

“You said it wasn’t funny!”

“Now it is!”

They both started laughing. They sounded like two baby elephants cavorting in a mud puddle.

An old couple drove past, in an old car, slowly, like a police car looking for a suspect. The interior of the car was dark, the air stale and motionless. They stopped the car.

“Goodness, Henry,” the old woman said to her husband. “What are those two girls laughing at? It’s like they’re having seizures!”

“Girls should be locked in an upstairs room with no windows,” Henry proclaimed sternly.

“Chained to a radiator!” Gladys cried, staring at the girls.

“Disgusting!” Henry blurted.

“I’m glad we never had any girls! You never saw our boys laugh like that,” Gladys roared.

“They might as well be naked, for Heaven sakes!” Henry added.

“Dreadful!”

Sometimes the girls’ laughter sounded like the laugh-track of a 70s sitcom. Sometimes they laughed so hard they cried. Sometimes they laughed so hard they almost wet their pants.

All the while, cars filled with old people pulled up next to Henry and Gladys. They had never seen two girls laugh with such intensity. Jowls flapped with indignation.

Brandy and Cheyanne laughed for days. Soon enough, the people from the Guinness Book of World Records arrived with their team of accountants. They were having trouble, though, determining the exact time at which the girls had started laughing. The only people they could find who were there at the beginning and who might be able to help were Henry and Gladys, who wanted no part of it. The accountants soon gave up and headed back to their headquarters.

WHHY, the local television station, sent their crack news team – Biff Gordon, reporter, and Liam Seymour, cameraman – to “get to the bottom of the situation,” as they say at the start of each newscast. Their van, with a large satellite dish on the roof, beamed live updates to living rooms across the region every half-hour and drew more oldsters to the scene.

The sight of Cheyanne and Brandy made the spectators want to scream.

Sometimes the laughter sounded like a thousand helicopters all taking off at once. Sometimes like the hiss of a snake. Sometimes the laughter sounded like the siren wail of an emergency vehicle.

“What draws senior citizens, such as yourself, here to watch these two girls?” Biff asked a wizened old woman in a wheelchair. Seymour’s light illuminated every wrinkle on her face and every white hair above her lip. On her lap sat a shivering Chihuahua wearing a custom-fitted gray cable-knit sweater.

“What these girls are doing is just plain wrong!”

“They’re simply laughing,”Biff responded.

“They need a spanking! They’re too loud! They’re selfish little brats! They’re like exhibitionists! Flaunting it, taunting us!”

“What are they flaunting?”

“Back in my day…”

The old lady began coughing into a handkerchief with a doily border, and waved Biff and Liam away.

Sometimes the laughter sounded like a braying donkey.

As the days passed, the atmosphere changed. The air grew muggy with derision, yet the girls continued laughing, as if oblivious to what was happening around them. People wondered what kept them going, and others hated them all the more for their childish stamina. Before, the old people felt like they were visiting a freak-show. Now, they felt like they were soldiers digging in for a long siege.

Sometimes the laughter sounded like machine-gun fire.

“Stay the course,” the elder-warriors told each other.

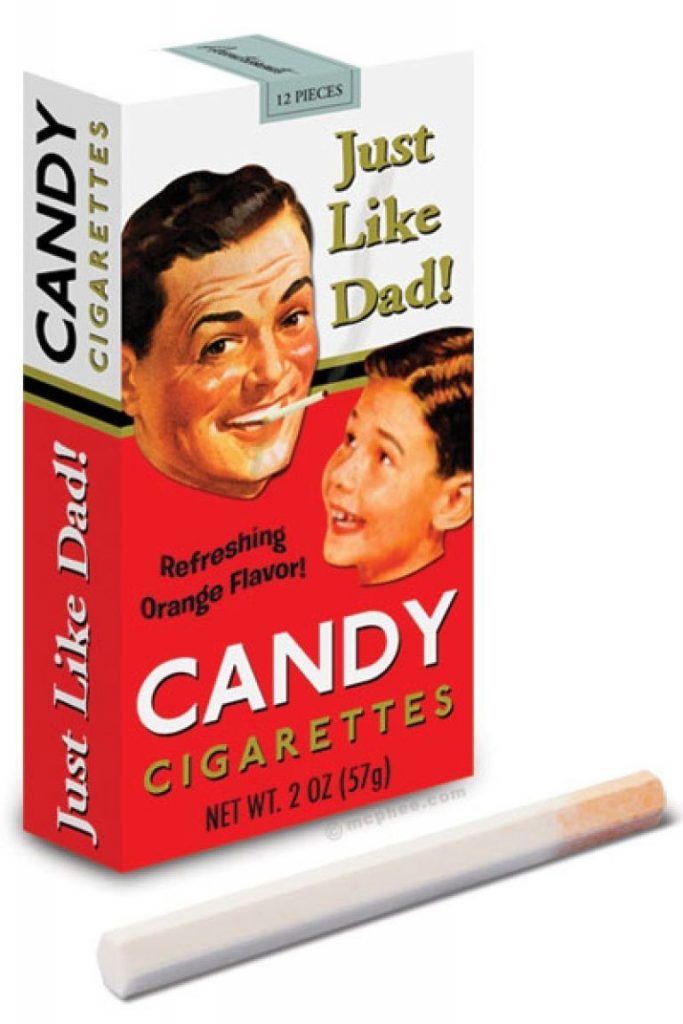

Seniors continued arriving at the scene of the exhibition. They brought hard candy and tissues and walkers and canes. The town had never had so many people in one place.

Sometimes the laughter was like the sound of bombs exploding.

The sounds of cane-tips hitting the ground, the sounds of coughing and the spitting up of phlegm, contributed to the geriatric din of hatred and intolerance that competed with the laughter.

And then there was silence.

After the leaves had fallen from the trees, and the mornings were covered with frost, a boy on his way to school approached the end of the stone-and-cement retaining wall where Brandy and Cheyanne had sat until recently.

“What the heck?” the boy asked himself. Where were the girls?

A chill down his spine, for what he saw looked like that terracotta army in China: thousands of senior citizens, all facing the end of the retaining wall where Cheyanne and Brandy had laughed, and all turned to stone. The boy ran back home.

Looking back on what had happened, Liam Seymour, cameraman, thought that it was the most bizarre thing he had ever witnessed. Thousands of old people had surrounded these two girls like a pack of vigilantes surrounding a hoodlum who had stolen an old lady’s purse. At one point he thought they were going to start throwing rocks at them.

Fortunately, he had taken a ton of footage, much more than the station ever used, but that was always the case. He kept all of it on its own hard drive, and put it in the back of a desk drawer. He especially liked the shot he took of an old guy hoarsely yelling obscenities, face contorted in anger, gray watery eyes bulging, lips sunken because he had no teeth to support them, and turning to stone in mid yell. He played that over and over again for a while, in slow motion, that transformation. That hardening of the skin, the darkening of the eyes.

For a while, Liam Seymour had trouble sleeping, and he became over-protective of his own two kids. Science tells us it is impossible for a human being to turn into stone, and he hadn’t been the only one to witness it.

More importantly than how, to Seymour, was the question of why. He had theories, but it would take a lot beer for him to discuss them. Something about change.

Sometimes the laughter was deafening. Sometimes you had to hold your breath and stand still like a statue to hear it.