“When art so brazenly embraces darkness, I take notice.” An essay which celebrates the dark themes and imagery of Scott Walker’s avant-garde music which helped one writer strengthen their craft and pursue their niche…

by: Jennifer Worrell

Artists who experiment outside trends and popular tastes, whether in literature or music, have always triggered my imagination. I’m fascinated by fiction that plays with form and derails expectations.

My admiration likely stems from lifelong imposter syndrome, always the novice despite years of experience. How can I recreate the magic expressed by my influences? What exactly will capture an editor’s eye? Deviations from the norm are much better received — and marketed — than escapes into unexplored tangents. But those tangents have a delicious allure. Cryptic narratives intrigue me. The spontaneous and indefinable seduces with a call I can’t ignore, imploding the typical and erasing the borders of what the human mind can produce.

I recently became obsessed with Scott Walker and his nonconformist late-career music. That is, Scott Walker of the pop group The Walker Brothers, not the former U.S. governor, although it would have been interesting to hear “No more dragging this wormy anus / ’Round on shag piles from Persia to Thrace / I’ve severed my reeking gonads / Fed them to your shrunken face” emanating from the former Wisconsin representative at a campaign rally.

My introduction to Walker’s music was his band’s 1966 cover of Bob Dylan’s “Love Minus Zero.” When my husband introduced me to Nite Flights (1978), the last official Walker Brothers album, I dismissed Scott’s operatic baritone as cheesy until I heard “The Electrician.” The buzz of anxiety, intrigue, terror, and beauty of “The Electrician” both attracted and repelled me. The tremulous strings and deranged lyrics (“Baby it’s slow / When lights / Go low / There’s no help / No”) led into a sweeping, passionate bridge reminiscent of Spanish serenades. Was I meant to be repulsed or romanced? The juxtaposition kept me deliciously off-kilter: the charming monster confusing its prey, luring it in with heady lushness, paralyzing the victim’s instincts to flee. I actively seek out this track the way other people put Gaga on repeat. Considering it’s about a CIA torturer delighting a bit too much in his task, I wonder what that says about me.

Walker’s shift to disturbing avant-garde work was likely the reason behind the band’s demise. The other two members stepped back from the bleak abyss he was leaping into, while fans with similarly twisted sensibilities reached out their arms.

Lately I’ve been restless, impatient to advance my skills and career and grasp this elusive form. As though able to read my mind, a friend invited me to a transgressive fiction workshop. We explored our compulsions toward the extreme, dissecting ideas like students in a literary appreciation class, an approach I’d yearned to revisit since my jerry-built college days. Though humbled by the knowledge and talent of the other members and completely unsure whether my black satire fell anywhere in the transgressive ballpark, I meekly dropped a little excerpt in the chat. When one member let out a whoosh followed by an approving “wow, that was dark,” I felt like a door had been opened.

After discovering Nite Flights, I moved on to Tilt (1995). At first, Walker’s distinctive voice calling “Do I hear 21, 21, 21? / I’ll give you 21, 21, 21” seemed laughably incongruous, his menacing tone clashing with silly lyrics. But the song (“Farmer in the City”) built, one shredded note at a time, like a horror movie whose protagonists shrug off the oddities of locals until they’re locked screaming in a torture chamber. Add skin-crawling crackles and moaning both human and otherworldly in “Cockfighter,” demented wind chimes and urgent drum beats in “Bouncer See Bouncer,” and you have the soundtrack of nightmares. Like those graphic horror movies, this album sunk its teeth in, every eerie transmutation forcing hypervigilance, lest the monster take hold completely.

Tilt is not the kind of thing you should listen to while angry. Or nervous. Or while trespassing at the site of your former workplace’s demolition. The CD played as I drove home after an unremarkable errand run. I screeched to a halt in the middle of the once-familiar street, shocked to see my old publishing house battered, glass shattered and roof collapsed, guts spilling into the dusty parking lot. Never had I worked somewhere so dismal and demoralizing. To see the place crushed the way the job crushed my soul was a lovely bit of vindication. I itched to wallow in it, revel in the desolation and commit the wreckage to memory. So I hopped the fence to gawk.

Apprehensive at being caught by the cops, having to explain why I was taking pictures — or worse, getting injured without a way to summon help —added to the disquietude. A graveyard minutes before sundown. Percussion reminiscent of spanking and Walker bellowing “Hey you / Hey you! / This isn’t through” in “Bolivia ’95” scored hazy flashbacks I didn’t want to relive yet savored with a jittery schadenfreude. The contradiction of “The Electrician” mirrored in real life. I found release as I kicked bits of concrete walls that once held me down, ground glass beneath my feet. Here was the site of my own six-year horror show, but all that remained within the rubble and bones was music and memories, both I could shut off at will. Scott Walker’s angst poured into his art; I quelled mine by immersing in it.

The cathartic motif continued with The Drift (2006). Consider “Clara,” inspired by Mussolini’s mistress, who insisted she be executed alongside her lover. If the percussion sounds unusual, it is. According to the liner notes, that’s Alasdair Malloy’s staccato punching of a side of pork.

Reading about Walker’s inspirations led me down countless rabbit holes. I spent hours researching his music, pored over endless articles and interviews, ordered every album even tangentially associated with Walker from my library to study his eclectic methods in production and voice. Through immersion I’d develop skill, intuition. Recreation through osmosis.

It’s rare I spend this much time in another artist’s world, especially one whose music has been defined as challenging and difficult. But with commercial radio’s often monotonous and repetitive offerings, such a challenge was refreshing. I’m drawn to art that embraces the unusual, the unspoken. Art for art’s sake, as opposed to popularity or money.

The same is true of my reading habits. I hunt down books that mix genres, study literary styles that defy conventions, or emulate techniques less familiar in Western culture. Storytelling takes so many forms, but often what I find on the shelves — whether in albums or books — feels like more of the same. When art so brazenly embraces darkness, I take notice, with a pressing desire to find my own work among them.

Bish Bosch (2012) may be the most unsettling of the three albums I’ve heard so far. I’m uncertain whether Walker was as furious as he sounds on “SDSS1416+13B (Zercon, A Flagpole Sitter)” or he was simply an amazing actor, but I was immobile for all twenty-one minutes of the protagonist’s mad frustration, as though waiting out the end of a punishing tirade. The song is a story-within-a-story from the point of view of Attila the Hun’s jester. By spinning tales, he finds freedom through the halls of his own imagination. Isn’t that what we’re all doing? Trying to make sense of the world around us (even more, these days), looking for a little escape from madness.

Like Christ’s Descent Into Limbo (the painter of which inspired the album’s title), the ominous atmosphere compelled me to focus despite my discomfort, engrossing me in its depth — sometimes bordering on suffering — experiencing emotions that daily life tends to skim over and polite society has no idea how to manage.

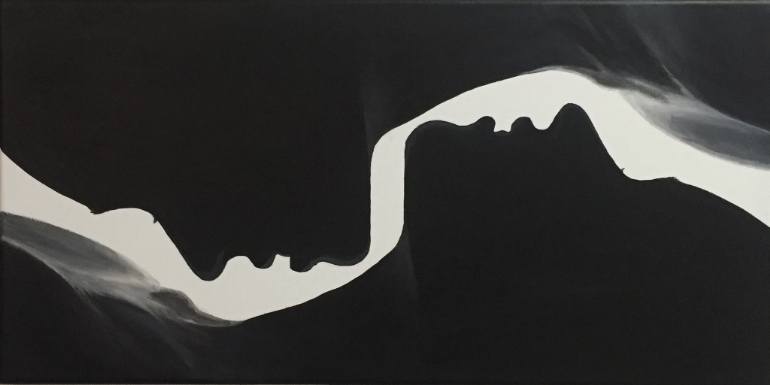

Though often leaving my stomach in knots, there’s undeniable beauty in Walker’s late-career music. In a world where we’re often pressured to choose between black and white, his music reminds me of all the gradations between, the conflicting nuances that force us to confront life’s bleakest corners.

Perhaps with the bombardment of overproduced pop and the dissolution of entire genres as I knew them (RIP, country), Walker’s calculated efforts make me feel something substantial. Even if it is blacker than I’ve been able to create myself. Perhaps because of that reason. To be able to produce something that visceral and macabre must be epically freeing. Knowing that the path has been paved — and there’s an audience for it — brings an unexpected ray of hope.