“This city’s wild chaos was the new Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil.” A search for God, and for community, in the big city leads one man to the Open Arms Fellowship and the mysterious happenings of its sub-basement…

by: Danny Anderson

In the bleak midwinter, the lobby desk was a warm comfort. I ran my fingers across its sharp lines and varnished, deeply scarred top. The desk was an unmovable, wooden relic of the old building’s stylish, mid-century past, and I was its partner in the present. I sat behind it like a throne each Thursday night, in a high-backed office chair of purple leather, from 7 until 11. At that moment, the door to the cold city was finally locked tight.

New York was frigid and gray on winter nights and I had nowhere to be. I was new to the city, and though my old Midwestern life had prepared me for the shearing winter winds of an East Coast February, it had not taught me how to penetrate the swirling, sophisticated social circles that made the city such a beacon for the restless. A job on the floor of a posh, uptown Big Chain Bookstore was how I ate and paid for my room, which was even more uptown, beyond all poshness. The room was warm and dry, but not home, so I eagerly sought places to be what I called “in the city” at night.

Thursday nights, I found my spot in the city at the reception desk of a midtown mission. Open Arms Fellowship was the church I’d been attending since moving to town. The radical break with my old life set fire to a spiritual crisis that bordered on desperation, so it was natural, even cliché,for me to search for God in the mean old city. There was, of course, also a deep longing for human community that, if I’m honest, was the primary motivation for my attendance. I ached for the company of mere mortals. To the customers at the bookstore, I was barely distinguishable from the books or keepsakes for sale in its four-stories of merchandise. And my co-workers fled straight to the stuffed subway cars that rushed them home to the boroughs after work. When a call for volunteers came from the pulpit of Open Arms, I signed up. And for the next several weeks, I spent Thursday nights at the great oak desk, comfortable with a sense of purpose.

It was the last night I would ever sit at that desk. I heard the lobby door open and looked up from my book. I greeted him as he walked in, striding confidently across the lobby towards me. He had followed the burst of freezing air that pulsated through the lobby when he opened the door, breaching the barrier that kept the cold hearts of the city at bay. I had never seen him before, but he smiled widely.

“I’m one of Tony’s guys,” was all he said. It was all he had to say. The man I knew only as Tony ran a shelter for homeless men who were holding down jobs in the city. There were beds and lockers downstairs and knowing the name Tony was the key card.

The church was in an old firehouse that had been repurposed by a group of Christian hippies in the early 70s. In their zeal to save the city they created a chaotic, beautiful space of worship and service. Behind me was the darkened room where Sunday services took place. In the three floors above me where the offices and storage rooms that kept the fires of Christian mission burning in these last days.

There were two floors below us. The basement and the sub-basement. The basement had a kitchen and pantry which fed Tony’s guys and innumerable other hungry, savvy clients, including me on Sunday afternoons.

Tony’s guys stayed in an open room with a dozen beds in the sub-basement. The space opened to Tony’s guys at six each evening and they had to be in by nine. In the morning, they had to leave by eight. As long as they produced the weekly pay stubs that proved gainful employment, they could stay for six months. The idea was that in half-a-year, they should be able to save up enough to live independently as responsible adults. The philosophical tradition of Christian bootstrapping in action.

This particular “Tony Guy” was dark-skinned and, based on his accent, I assumed he was from India or Pakistan. The world I’d come from did not expose me to much cultural diversity, and I felt conspicuously ignorant about such matters, so I greeted him with an embarrassing amount of cheer.

“Well okay! Welcome back and have a great evening!”

He nodded and pressed the elevator’s down button. My desperate greeting made the twenty-second wait excruciating for both of us.

“Bye,” he said, as the elevator door rattled shut between us.

Alone again, I released a deep breath, looked at my watch, saw that it was 9:18, and returned to my book. I was starting a new biography of Che Guevara that had caught my eye at the bookstore. Earlier that day, I had picked it from the floor, perused and discarded by someone we still called a “customer” for some reason. I looked at it perhaps too quizzically, struck by the iconic image of Che and his militant beret, drenched in bright colors for this particular release. My floor manager, Gary, saw my interest and, in an attempt at apologizing for halting the pace of my work, I asked him who Che was.

I could feel the shocking weight of my ignorance in the lines that appeared on Gary’s forehead and around his tiny mouth as he processed my question. He politely explained the broad brushstrokes of Che’s biography: Cuba, Castro, Bolivia, and I nodded with intense interest and bought the book on my way out, as if to prove something.

Looking at that biography now, still in the moment of this latest humiliation with Tony’s Guy, was a bit much and I needed a minute. I tossed the heavy book down roughly into the solidness of the oak desk and stretched back in my chair, arms reaching far over my head. I rolled the chair back, stood up, and walked the checkered tile floor of the lobby, taking in the old architecture and design — art deco? I’d heard the term, but I didn’t really know. I stopped at the thick wooden front door and peeked through the diagonal steel grate over a small, smoky window, no bigger than my face.

I could not see through the window and, feeling the loneliness of the lobby, I opened the door and stood, taking in the cold wind I rubbed my hands up and down my arms as I looked at the city around me. The streets of midtown were never empty, but they were quiet in these evenings. People walked past me, some alone, some in groups. In my relatively brief New York experience, I quickly learned not to attempt eye contact or the nodding head I’d always instinctively greeted strangers with, so I simply let them pass and in doing so I became one with the lonely city. I let the strangers remain strangers and they returned the courtesy.

I filled my lungs with gallons of icy air and turned to go back in. Just then, Parker approached, walking toward me from 9th Avenue. I smiled and waved and he greeted me.

“You locked out?” He asked. I wasn’t sure if his question was motivated by concern or annoyance.

“Oh no,” I said. “Just catching some fresh air.”

“In this city?” Parker joked. He was from even deeper in the Midwest than I was and seemed to hold those extra miles as a grudge against New York City. Like a hick, desperate for friends, I shrugged my shoulders and laughed too heartily.

“I was just going back in,” I said. I opened and held the door for him.

Parker was not the pastor of the church. He was more like the office manager, though his title had a more sacramental sound to it: “Pastor of Ministries.” From what I could understand about his job, he oversaw and managed the various mission-related activities the church operated out of the crumbling old firehouse. I imagined that his typical day was occupied with grants and volunteer-wrangling and giving speeches to donors. When I first walked into the open arms of Open Arms, I instantly recognized a fellow Non-New-Yorker in Parker. His khakis and pastel button-up shirts screamed “Nebraska!” to my Indiana eyes. He was quite a bit older than me and much more immersed in the evangelical tradition that valorized “saving the city from its iniquity” than I was. So we had just enough in common to make it immediately obvious that we weren’t going to be friends. His mind was laser-focused on a fast approaching apocalypse, so to him I wasn’t a serious person. And, in truth, he was right. I had come to the city with an entirely different delusion. I had imagined New York as a great sandbox of energy and chaotic invention where I could dismantle myself and rebuild with spare parts I’d find in the streets, bookshops, and open mic nights. Our individual imaginations had failed us in entirely distinct ways and we were left to simply tolerate one another. But we did that very politely.

“Anybody come in tonight yet?” he asked.

“Just Tony’s guys,” I replied. “That’s pretty cool work he’s doing,” I added. Parker looked at me the way Gary had earlier that day when I asked him about Che Guevara.

“I’m just glad Tony’s willing to handle all that,” Parker said, gesturing dismissively, with a dash of disgust, at the floor under our feet. “I guess he’s uniquely prepared to do that kind of work.”

I had met Tony twice. He rarely came up during my shift and never spoke when he did. I would occasionally see him on Sundays in the room behind the oak desk. I did hear his testimony one week, though. He was once a successful accountant but a drug addiction had derailed his career and landed him in prison for embezzling. When he got out, his family would have nothing to do with him and he found a home on the streets. His eyes bulged and he wept as he told the congregation this story. His tears were real and I never doubted that. Eventually, he landed in a homeless shelter that turned his life around and that, dear believer, is the inspiration for the Open Arms Working Men’s mission. Please consider a donation.

I was moved by Tony’s story, but was afraid of Tony. He brought a blunt humorlessness to his social interactions, which I did not and do not blame him for; I took his manner as a necessary tool for surviving a life like the one he was still surviving.

I went back to my desk and covered the book I was reading with a New York Post that someone left behind. I didn’t think I was afraid of him, but I wasn’t ready to find out what Parker thought of Che. Parker walked into his office and I sat back down, returning the biography’s first chapter.

I had turned three pages by the time his office door opened and Parker walked to the elevator, where he pressed the down button hard and repeatedly. He kept his back to me and said nothing, so I kept my book out in plain sight.

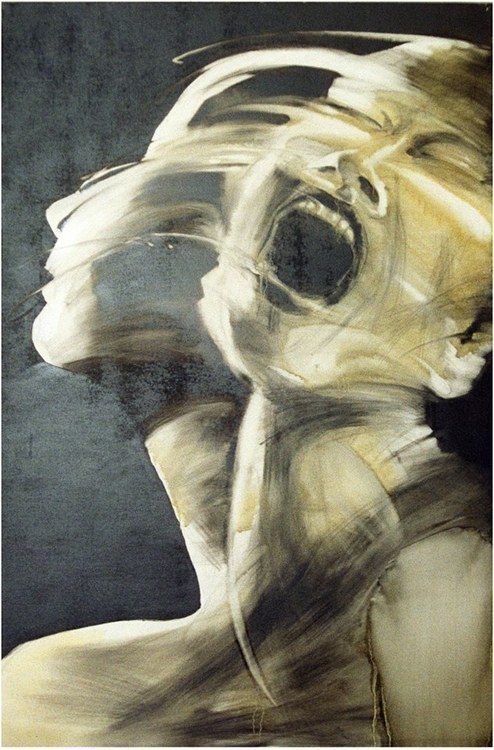

The lobby was quiet again and I closed my eyes, taking in the sounds that muffled through from the street. An engine accelerating. The squeal from the stressed brake pads of a box truck. Distant sirens. And, as always, the arrhythmic symphony of horns that gave the city its soundtrack. So many people and so many machines. All in motion, circling round and round each other, somehow only rarely crashing together to create out of the nothingness a new love, a profitable business opportunity, or a tragic street crime. I slammed my book shut, threw my crossed feet up onto the heavy desk and interlaced my fingers behind my head. I looked at the tiny, opaque window in the heavy door that kept the city at bay, and I watched the lights roll across it. All at once, a knowledge that was not quite wisdom drowned my senses. Blinded and deafened by understanding, I instantly understood why so many people sought out New York City and why they came at all their neighbors with such alert, pointy elbows; everyone was ravenous. This city’s wild chaos was the new Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil. I felt the holy epiphany descend on me and was awed by the vision of unstained beauty in the all alienation that swirled madly around me.

Like a mesmerized audience volunteer yanked from his hypnotic state by the snapping of the hypnotist’s fingers, my moment of tranquil enlightenment was shattered by the heavy, echoing footfalls stomping up from the basement stairs, around the corner from the elevator. Someone was exploding up out of the basement and they were skipping steps. No one ever took the stairs, so my heart began to mirror the heavy pace of the pounding feet that drew near.

Crashing through the door came Tony’s Guy, the one I’d greeted earlier. The metal door, graded for fire safety, hit the wall hard and shook as it returned, slamming back shut. The plaster where it struck was pulverized into a powder that fell across the floor and shot a white cloud in the air, which hung, then fell like ash. A black hole shone through that wall now and Tony’s Guy ran to me, his hands crying out for mercy. His wild eyes were not filled with anger or tears, only terror. I pulled my feet off the desk and sat up, digging my fingers deep into the purple leather of my chair.

“Please please! Help me, sir.” His voice crackled, just below the register of a scream. I raised my hands, signaling my utter helplessness against his pleading. The man kept begging, “please please,” and his body shook. A cold wind whispered through a cracked window across the lobby. The man aimed his panicked gaze at the source of the howling whistle and he sobbed. Over his shoulder I saw Tony, then Parker emerge from the stairway. Tony walked to him without emotion and stopped just behind him. Parker’s face shone with cocky righteousness, while Tony’s was still chillingly flat. Parker looked like a man who had found glorious purpose and Tony looked like he was ordering a sandwich he didn’t really want.

“Come on man. Time to go,” was all Tony said as he put a heavy, yet gentle hand firmly on the elbow of his former guy.

“But I didn’t do anything! You can’t do this to me! Please!”

Tony replied with dead, black eyes that never blinked or looked away. “The shelter’s rules are black and white. You have to be in by nine. And you’ve had more than one warning. It’s out of my hands.” Tony was blunt and direct in all things, and he only seemed to speak in short, basic sentences that would make Strunk and White proud. For Tony, all of life was “subject, verb, object” and his sentences reflected that philosophy. He barked his words like a guard dog. And with his bulky torso and thick black hair, he indeed looked like an animal who might be guarding the junkyard at night in an old movie. He neither enjoyed, nor regretted this confrontation.

“But I swear!” was all the man could say. It was if he’d started a thought with no idea where it was going and then gave up finding it. Tony said nothing. He just blinked his eyes with terrible slowness and shook his head. The man craned his neck and looked around Tony, to Parker, who had been standing silently with his arms crossed.

“Please sir, you can’t make me leave tonight. I have nowhere to go.”

Parker uncrossed his arms and scowled as he shot an accusing finger around Tony, into the man’s chest. “You talk to Tony,” was his final word.

Tony said, “We have a waiting list for those beds and we have rules to keep,” and he left it at that.

As he spoke, Tony was already ushering the man, with an insistent push on his arm, toward the door. The man looked at me with wide, broken eyes, full of red and bulging with water, as he was pushed out of the warm safety of Open Arms.

“But my things in my locker!” he said to Tony from cold on the other side of the door.

“We’ll have them boxed up and ready for you in the morning. Eight sharp.” And with that he tossed one more lonely soul at the city, which would gladly churn the man into its dazzling vortex of American striving. Tony shut and locked the door, patted Parker on the shoulder and walked back down the stairs into the basement. He never even looked at me.

I watched him disappear, back down into the stairwell. When I looked back, the door to Parker’s office was already shutting tight behind him.

After a few minutes that might have been years, my heavy breathing slowed to something like normal and I could feel that tightening ache deep in my throat, which I knew would soon transform into tears.

I jumped from my chair, threw on my jacket, and left my book on the desk. I would save my tears for the frigid streets of Hell’s Kitchen, not waste them in the peace and safety of this church and its many missions. I threw open the front door, unleashing arctic Hell on the lobby, and willingly heaved myself into the open arms of a craving city.

Danny Anderson has published stories and essays in a variety of publications, including, Litbreak, Dream Pop Press, PopMatters, Film Inquiry, and his Substack, UnTaking. He lives and works in the Laurel Highlands of Pennsylvania. He can be found on Twitter @dannypanderson.

Header photograph by Peter Kolejack.