A story which takes place in a time of renewed hope for America in which a group of boyhood friends take their frustrations out on the world armed with eggs. Cartons and cartons of eggs…

by: Michail Mulvey

It was 1961. I was fourteen. John Kennedy lived with his wife Jackie and their two kids in government housing at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. I lived with my mother, stepfather, and half-sister in city housing at 42 Merrell Avenue.

With nothing to do one damp October night, I wandered the brick and concrete canyons of our housing project, kicking cans and banging on signs with a stick. I usually ran with a pack of kids from the projects, but my buddies had all gone home. It was cold, late, and a school night. Truth be told, I was avoiding my mother and step-father, who, when they weren’t drinking and arguing about some stupid shit, sat simmering in front of the television, one beer away from another brawl.

Chilled through and bored, I was about to take the elevator up to our sixth-floor apartment when I noticed a trailer, the rear end of an eighteen-wheeler, parked on Edison Street, a side street behind Building B. It caught my eye because it looked out of place, sitting there in our neighborhood a long way from any supermarket or department store.

Wondering who this trailer belonged to and what it was doing in this part of town, I walked over and checked it out. There were no markings on the side and no lock on the rear doors, so, naturally curious, I opened them. The doors were heavy and made a creepy creaking sound. When I saw the contents of this trailer, I knew that some very stupid person had made one very big mistake.

Before me were eggs. Cartons and cartons of eggs. There must have been a thousand cartons filling this trailer from front to rear, floor to ceiling. For a minute I just stood there staring at all these eggs, left in a trailer on a dimly lit side street next to a city housing project filled with kids like me.

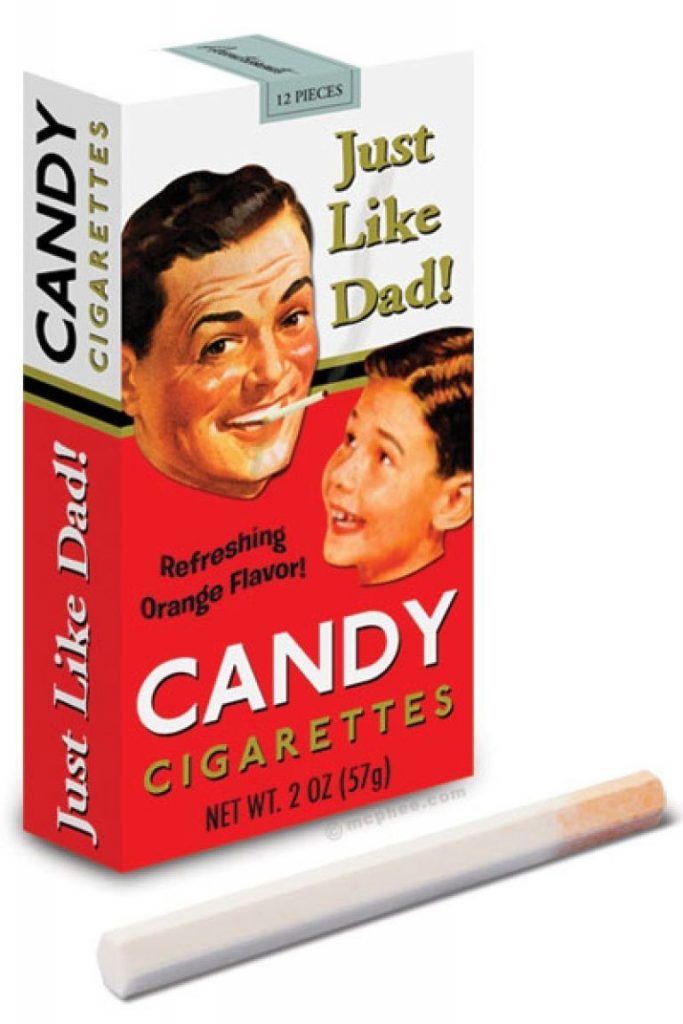

I reached up into the trailer and grabbed one of the cartons: ‘Grade A Extra Large’ it read. A Sunday morning television show came to mind. A farmer was holding eggs, one by one, up to a light, checking to see if the embryo was fertilized or not. ‘Candling the egg’ it was called.

I opened the carton, took out an egg and held it up to the streetlight, but the light wasn’t bright enough to reveal the contents. I tapped on the egg with my finger. “Anybody in there?” I asked. Even though I knew I’d probably get no response, I held it up to my ear anyway.

If there was a chick inside, he must have felt cold and alone, even though he was sitting in a carton with eleven of his buddies, all lined up in two neat rows. How do they breathe in there, I wondered. Curious, I cracked the egg open on the edge of the trailer. Just as I had suspected, there was no chick inside, just runny egg snot and a round yellow yolk.

Eager to share my discovery, I ran back into our courtyard, a parking lot for the families who lived in buildings A, B and C. All together there were a total of nine, neatly arranged six-story apartment buildings in Vidal Court. Lettered A thru J — for some reason the city planners left out the letter I — there were twenty-four families per building, each having, on average, at least two kids, sometimes three or four. I made some quick calculations in my head: nine buildings, times twenty-four families each, times two or more kids, divided into a thousand cartons of eggs; I wasn’t all that good at math, but even I knew the possibilities for mischief were infinite. With that many kids and that many eggs, we could cover half the city in runny egg snot and yellow yolk.

I would share my discovery with only a select few, my best buddies — Mickey, Georgie, and Robbie — fellow juveniles who some called my partners in crime.

“Come see what I found,” I whispered to each when they came to their doors.

Mickey complained he was in the middle of an episode of Ozzie and Harriet. “Shut up and put your shoes on,” I told him.

“I gotta watch my sisters,” said Georgie, whose mother worked the night shift at a meat-processing factory in the south end. His two little sisters stood behind him at the door. Curiosity got the better of him, however, so he turned on a cartoon — Rocky and Bullwinkle — sat the two girls on the couch in front of the television, gave them a bowl of M&M’s, and came anyway.

Bored and alone, Robbie grabbed his jacket and followed us.

When they had all gathered at the rear of the trailer, I opened the doors and watched their faces as I revealed mydiscovery. “Holy shit,” said Mickey, “look at all the friggin’ eggs!”

Georgie reached out and gently touched one of the cartons, like he couldn’t believe his eyes. Robbie just stood there, mouth hanging open in disbelief. We looked at each other for a moment then smiled a knowing smile. We gathered as many cartons as we could carry and proceeded to look for targets.

We started with the trailer, figuring anyone stupid enough to leave a whole trailer-load of eggs in our neighborhood deserved to have their property egged. We each tossed about a half dozen. Our arms warmed up, we turned and pegged the rear of Building B until some old man opened one of the egged windows and yelled, “Hey, what the hell are you kids doing? Dolores, call the cops!” We laughed and ran off.

We headed for Building G, peppering the rear of buildings D, E, and F along the way. We were looking for one particular window on the fourth floor of Building G, the bedroom window of a girl named Margaret — nicknamed Large Marge — who some of us knew to be a tease. To fourteen-year-old boys, that was a felony. We weren’t sure which window belonged to Marge, so we egged about a half dozen on her floor. Robbie would have loved to egg Marge herself, covering her with yolk, but he didn’t have the nerve to call her out. He knew Large Marge would have kicked his ass.

We left the projects and headed for Stillwater Avenue, up the hill from Building G and around the corner. Stillwater was a boundary of sorts between an old Italian neighborhood — a mix of older single-family homes on tiny lots and triple-deckers — and the upper-middle-class suburbs of the west side. The projects were the tainted meat in a sandwich made with two slices of angry white bread: Wops and WASP’s.

We hid in an alley across the street from Dan’s Grocery. Dan didn’t like kids from the projects and kept a close eye on us whenever we dropped in for a cold soda on a warm day. One afternoon Dan came up to us as we stood around his magazine rack. Hands on hips, he told us some punks had broken in the night before and had heisted some soda, candy, and comics. “They tried to pry open the register but didn’t get nothing,” he said. By the look on Dan’s face, we were his number one suspects. He snatched the Spiderman comic out of Robbie’s hands and told us all to take a hike.

Dan’s was closed, but a faint glow from the milk cooler acted as a night light, illuminating the contents of the cooler which included milk, eggs, and cheese — an omelet.

“How do ya want your eggs, shithead?” yelled Robbie as he hurled an egg at Dan’s store-front window. “Hope you like ‘em scrambled.”

“Breakfast is served,” yelled Mickey, aiming for Dan’s door.

“Take that, asshole!” yelled Georgie, firing egg after egg. Georgie hated Dan as much as Dan hated us. Dan threw Georgie — whose real name was Jorge — out of his store one Saturday afternoon, complaining Georgie was spending too much time hanging around the magazine rack. Georgie later confessed to me that Dan had caught him checking out the April Playboy centerfold.

Each of us emptied the contents of at least one carton, then stood and admired our work. Yolk ran down Dan’s window in rivulets. Shell fragments and yolk littered the sidewalk in front of his store. We knew we’d probably be at the top of Dan’s list of suspects the next day, but we didn’t give a rat’s furry fart.

“Boy, is he gonna be pissed,” laughed Georgie.

Satisfied, we jogged up Stillwater Avenue, joking and tossing eggs along the way. We egged Lupinacci’s Liquors, a STOP sign, signs that said NO PARKING, a traffic light, and each other. I took an egg in the side of the head and Mickey caught one in the crotch. When Robbie ducked, Georgie took one in the chest.

We hung a right at the light, heading back to the projects. Up to the roof of Building J we flew, passing the elevator, taking the stairs two at a time. The door to the roof was locked but Mickey was able to pry it open with a knife. Below us lay Merrell Avenue.

We let several cars pass by, then rose up and quickly pegged about half a dozen. Anyone looking up into the night sky would have thought it was raining eggs. Most cars just slowed, honked their horns in anger, then drove off. One stopped, the driver got out, looked around and yelled, “I’ll get you, you little bastards!”

He was looking around, however, not up, so he had no clue where the eggs came from. Stifling giggles, our faces pressed into the cold tar and pea stone, we waited until we heard him speed off, burning rubber all the way to the traffic light at the end of the street, before peering over the edge. The street below was covered in egg yolk and shell fragments. Slimy egg white glistened in the light of the street lamp. Empty egg cartons littered the roof of Building J.

Out of ammo, we took the stairs back down to the street and headed for the trailer, watching for any egged cars that may have circled back hoping to catch ‘the little bastards.’ Each of us collected a couple more cartons, not as many as before, just enough to egg the rest of our world.

Figuring we should probably work another area, we left the projects and jogged one block north to Broad Street, a busy thoroughfare on the west side, a mostly suburban part of town, a section of town on which the city had dumped a city housing project filled with little bastards like us.

Halfway up the block, Mickey yelled, “Watch out,” and jumped into the bushes, pulling Robbie along with him. Georgie and I followed. A police car cruised by.

“Maybe we should head back,” whispered Robbie, a nervous edge to his voice.

“He didn’t have his siren or flashing lights on,” said Mickey. “So he’s probably just patrolling his beat…”

“…Looking for little bastards like us,” I said, chuckling.

Checking up and down the street first, we climbed back out of the hedge and continued on. We knew we’d find a better make of car on Broad Street. Newer cars. Expensive cars filled with guys who wore suits and ties. Cars filled with couples who lived in homes on multi-acre estates north and west of Merrell Avenue. Homes filled with people who played bridge and drank Martinis. Vidal Court fathers played poker in their t-shirts and drank Ballantine Ale from the can.

I was hoping the manager at Bloomingdale’s who’d chased me out of the men’s department thinking I was trying to lift a tie would drive by. Like I’d ever wear a tie. Or the old witch in the school cafeteria who thought I might stick a sandwich under my jacket. Or the librarian who kept an eye on me thinking I might steal a book or something. Yeah, right, a book.

We hid behind the hedges of a house, laid out our cartons of eggs and waited for the first Cadillac, Lincoln, or Chrysler New Yorker that came our way. We let the Chevys and Fords pass by, unmolested.

A Cadillac Coupe de Ville came into view. “They’re probably on their way home from Bloomingdales,” I whispered. “Or they just picked out a new sofa at Silberman’s,” said Mickey. “Or a new suit at C.O. Millers…” said Georgie, his voice trailing off.

Hunkered down on the cool, damp lawn, we waited until the Caddy got within range, then rose as one and pummeled it, firing volley after volley, aiming for the windshield and driver’s side window, hoping it was open, even a little. Stunned, the driver slammed on the brakes, got out and charged toward us, shaking his fist and yelling, “I’m gonna kill you, you little…”

Before he could finish his threat, however, an egg caught the guy between the eyes. Dazed, he stood there, yolk running down his face onto his shirt and suit jacket. Another egg hit him square in the chest, no doubt ruining his tie.

Despite his threat, we stood our ground and pounded the guy in the fancy suit and tie. Our arms were like windmills, hurling eggs as fast as we could get them out of the carton. Arms flailing, the driver tried to bat away the eggs, but in no time was covered in yolk from head to toe.

“Fuck you,” yelled Mickey, whose father was an out of work laborer.

“Yeah, fuck you, asshole,” yelled Robbie, whose divorced mother worked the four to midnight shift at some shit-hole restaurant on South Atlantic Street.

Georgie yelled something in Spanish, probably a swear.

In my anger, I grabbed one egg so hard it broke in my hand.

From inside the car, a woman screamed, “For God’s sake, Ralph, get back in the car! Get back in the car before they kill you!” In his fury, Georgie stepped over the hedge and stood on the sidewalk, heaving egg after egg with all his might. He was a big, easy-going kid who smiled and joked a lot, but tonight he was one pissed-off Puerto Rican.

Realizing he was outnumbered, the man in the fancy suit and tie, now covered in yolk, shook his fist at us one last time. He tried to bat away one last egg, missed, and took it in the head. He stumbled back to his car, shouting something at his wife as he got back in. He sped away, his wipers working to clear the egg off his windshield.

We were sweaty and winded, our labored breath visible in the cool night air. Robbie wiped his nose on his sleeve. I wiped my hands on my pants. Georgie stood on the sidewalk, empty egg carton in one hand, egg in the other, hoping the driver would turn around and come back. But the Coup de Ville disappeared around a bend.

“Let’s egg Mr. Cleary’s house,” I said, having no idea where he lived. Mr. Cleary was a much-hated math teacher who liked to belittle and slap students around.

“Let’s go to my mother’s restaurant and egg the owner,” said Robbie, who’d told us the old pervert wouldn’t leave his mother alone.

“Let’s go egg the crap out of the clubhouse at Hubbard Heights,” said Mickey who’d once told us about an old duffer who’d given him the up and down at the caddy shack one Saturday morning before picking the kid without the stained shirt and the scruffy US Keds.

But we were almost out of ammo. Empty egg cartons littered the lawn of this house on Broad Street, this comfy, single-family home with a porch and two-car garage sitting on a tidy, manicured lot with neatly trimmed hedges. The porch light was on but the garage was empty and the front parlor was dark. Nobody was home, it seemed.

We walked one block east and took a right on Shelburne Road, heading back to Edison Street, home, and the trailer. Checking to see if we were being followed, I turned and looked back up Shelburne. Single-family homes, identical in shape and color, all with two-car garages, all sitting on tidy, manicured lots, lined either side of the street.

“I hear sirens,” said Mickey, looking back in the direction of Broad Street. “Maybe we should call it a night.”

“Yeah, maybe we should,” said Robbie, rubbing his hands together, trying to warm them in the cool night air.

“I gotta go check on my sisters,” said Georgie, looking up as the night mist turned to a slow drizzle.

Mickey was probably right. Why push our luck. Besides, we were spent, our arms were heavy, and it was late. “Yeah, that’s enough,” I said to myself, once again looking back up Shelburne Road.

We stood in the street, smiling, sweaty and yolk-stained. Robbie’s jacket was ripped, Georgie’s pants were grass-stained and muddy. “My mother’s gonna kill me,” he said. Mickey held a shoe in one hand and a carton of eggs in the other.

“Breakfast,” he said, holding up the carton.

We had made a counter-clockwise journey, egging just about everything along the way, ending our night back where it began, on Edison Street, behind Building B. The trailer still stood there, filled with eggs from front to rear, floor to ceiling, waiting. But it was time to head home.

“See ya,” said Mickey with a smirk on his dirty face as he turned and headed back to apartment C-12.

“Yeah, tomorrow,” I called back, watching him limp away, still holding a shoe in one hand and a carton of eggs in the other.

Georgie smiled, punched me playfully in the chest, turned and left, hoping his two sisters had stayed put in front of the television.

Robbie just waved and ambled off, back to apartment B-14, where he would turn on the television and wait up for his mother.

I looked up, wondering if this drizzle would turn to rain and wash away the evidence of our night’s activities. Part of me hoped it wouldn’t. I looked over at the trailer and wondered if it would still be there tomorrow after school.

I took the elevator up to apartment A-63, slipped in and quietly passed by the living room where my mother and stepfather glared at the glowing television. I headed straight for the bathroom, eased the door shut, locked it, and tossed my egg-stained clothes in the hamper.

I filled the bathtub and climbed in. I washed dried yolk out of my hair, then leaned back and lay in the warm, soapy water, soaking, my head resting on the back edge of the white tub. I closed my eyes. A loud knock at the bathroom door and a, “Where have you been?” sent me sliding under, my head and face completely below the surface. The rapping on the door was muffled now, my mother’s voice a distant, almost inaudible mumble. Immersed in the warm water, listening to the beating of my heart, I wondered how long I could hold my breath.

Michail Mulvey is a retired educator. He has an MFA in creative writing and has been published in lit mags and journals such as Prole, Poydras, Summerset Review, Front Porch Review, Spank the Carp, Drunk Monkeys, Noctua, Umbrella Factory Magazine, War Literature and the Arts, and others. In 2013 he was nominated for a Pushcart Prize.

Well done. Reminds me of the kids from “Stand By Me”. Spiderman didn’t debut until 1962…