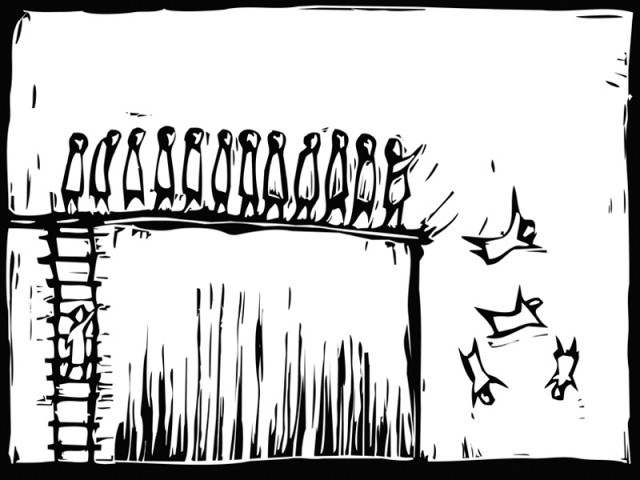

by: Nicholas Farriella ((Header art by Kelly Hutchinson.))

“Lying there, staring at the glow of an orange light overhead, I had visions of internet-based heavens and hells with ultrasounds being the middle ground between the two.” A deeply introspective short story where the push and pull of affection forces one to ponder the deeper meaning of it all…

It was the beginning of what the Farmer’s Almanac was calling a “dry summer.” When I read that on a rainy February afternoon in Raven’s Coffee Shop, I couldn’t really comprehend its meaning. It was like reading about how bad smoking is as you smoke a cigarette.

Four months later, sitting upon a ridge overlooking an arid lakebed, the term “dry summer,” was beginning to make perfect sense to me. Sweating and stoned my girlfriend Miranda and I sat looking out across a massive dust bowl of clay and mud. It was a three hour hike up to the top of the ridgeline, and we had stopped at various vantage points to look out and pass a one-hitter. After three hours, one expected a certain type of pay off, some exchange in currency of visual pleasure for time hiked. Yet, at the end of our footslogging, we were met with a landscape that could only be described as barren. Everything was dead and rotten. The trees were naked and dozed over in the mud, awkward in their bent bare state. Even the rocks took refuge away from the pit, jagged-looking, and reaching upwards towards the sky, towards an air of hope. In the pit of the lake, there were pointed skeletons of fish fossilized in mud. There was waste scattered around like coral reefs of garbage. There were wrappers, papers, beer bottles and cans, a Taco Bell cup, a few McDonald’s bags strewn about. It was as if Corporate America had staked its claim in the litter.

After staring out at the dried lake, a haze of insects hovering above its surface like a thin fog, we began to unpack our bags. We’d brought with us a blanket, a pillow, a canteen of water, a paperback book, and a solitary joint I had rolled on the car’s dashboard as we drove in. We made ourselves comfortable and I laid back to light the joint. A strong gust of wind blew over the lake, putting out the flame of my lighter. After three flicks, hidden in the cove of my hands, the joint ignited and another breeze passed through us.

“Do you smell that?” Miranda asked. She was lying back with her book resting on her stomach.

Yes, I did smell that. It was the raunchy stench of dead fish, a smell that my senses associated with the Jersey Shore. Days spent on docks on the bay, reeling up hook lines of crabbing cages.

“It smells like catastrophe,” I said.

Miranda laughed and for a second I forgot the tragedy that lay before us and took in her smile the way one takes in light. It was nice to sit with her. We had been so busy lately, on some sort of separate tracks of our own individual lives, that to sit down and do nothing from time to time seemed like everything. It was everything. Those minutes, minutes where we were inches apart from each other and I could smell her strawberry shampoo, just sitting and looking out at something sort of tragic, and still being able to laugh about it — that was us. In the future we could probably look back and remember the moment as beautiful. It was not beautiful, though. It was mortifying. It was like the end of the world and it was starting on a ridge in the heart of New Jersey.

Beside me, Miranda lowered her paperback and raised her eyes. She said something about coming here as a child when the lake was full. The glittering reel of the imagined memory showed a sparkling sun-kissed lake and a tiny Miranda in a one-piece bathing suit, swimmies on her arms, and learning to swim by fearlessly leaping from an old wooden dock. She asked for the joint and I offered her a kiss. I felt sublime.

After two more drags, my mood began to change. I couldn’t smoke anymore and I had the sense that I was becoming paranoid. The all-encompassing feeling of finality radiating off the dried-up lake, as if it was some sort of death sun glowing with bad energy, was seriously killing my high.

“I’m good on this,” I said, passing over the joint.

I watched as Miranda smoked and stared off into the distance. She inhaled and looked out into the pit, inhaled and looked at the shimmering horizon. I could tell she was deep in thought, contemplating something, or everything. At times I had no idea what she was thinking, whether she was enjoying her time with me or not. It may be that I didn’t see enough of her, but the times that we did hang out I was consumed with anxiety, questioning every remark, every expression. Was this good enough? Do you need anything? Are you good? These questions paved over any chance I had at enjoying something.

She bit her lip.

“The hike wasn’t too bad getting up here,” I said.

“The humidity is high,” she said.

“I think we left at a good time.”

“I’m hungry. Are you?” she asked.

“I could eat. We should have packed lunch.”

Miranda rolled her eyes back down to her book. Somehow the implication that I should have packed lunch fell on me. It wasn’t enough for me to find the hiking spot, pack the car with our things, and roll the joint (which I bought the weed with my last twenty dollars until payday), but I also had to pack lunch. This was a growing symptom of spending less time together, I surmised. There was an awkwardness between us, that was never there before. On top of that, Miranda stopped wanting to do things. It was always, “Mike, what do you want to do? What do you want to eat?” It was as if she had gradually become a passenger to our relationship, while I was in the driver’s seat hammering down the gas pedal.

After an hour of silence with Miranda reading her book and me stuck in my own head with my thoughts, we hiked back down to the road where her car was parked, a thin, snake-like road that slithered between two bulbous mountains. The scenery reminded me of a certain drive in which my father had the radio blasting classic rock, with the windows of his 94’ Toyota pickup truck rolled down, amid tall cliffs of mountains and forest with a strip of ceaseless pavement through endless green. I don’t remember which road it was exactly, but the one we were on now could certainly have been the same, except the green wasn’t as endless as it was in my memories. The forest spread before us seemed finite, bound to run into a highway, a shopping mall, a housing development, or a dried-up lake.

“That was kind of depressing,” Miranda said, starting her car. The radio sprung on loudly. A song from the 90s played.

“Wasn’t music, just better then?” I asked.

Miranda nodded and turned over the dial. Was it the instruments sounding different, as in maybe they were tuned differently back then that made it sound better? Or maybe the sound of today’s high-definition is too clean, and washes away any leftover feeling? My father had once said, when watching The Beatles fumble and yell through a set, “That’s the good stuff.” Maybe that’s what was missing, “The good stuff.” I gazed out of the window and watched what was left of the landscape blur past. For a moment, my thoughts fell away with the wind, blowing by aimlessly.

“Are you okay?” Miranda asked. “You’re quiet.”

“I’m not sure.”

And I wasn’t. I felt a sharp pain in my hip, running down into my groin, around to my lower back, and down my leg. It had started on the hike down to the car and had been throbbing ever since. I thought it could have been a hernia, but after Googling what a hernia actually was, my symptoms seemed a little off.

“Let’s go relax,” she said, and flicked the blinker up to get off at the next exit, the exit towards her apartment. The 90s alternative rock on the radio faded, making way for something new and awful.

Miranda’s apartment was on the second floor of an old brick and mortar building. It had been a large dance studio with high ceilings, but the owner of the pizza parlor beneath had grown tired of all the thuds of nightly dance classes and bought the upstairs, turning it into an apartment. He left the floors and the mirrors, and built a loft inside with a steel staircase that led up to it. It was incredibly hip, perfect for Miranda. When moving her in, I thought about how much energy flowed through the apartment, that she couldn’t deny how much foot traffic was once held in that vicinity daily. It was sort of like a Native American burial ground, which, thanks to the 1982 movie, Poltergeist, the chance of living on one was a legitimate fear to my eight year old self still inside me. After the first month of staying there, I wondered if there was a correlation between the thousands of dancers that passed through Miranda’s apartment at one time or another and my inability to get any sleep there.

Miranda was up on the loft, lying on her stomach on her bed and rolling a joint on the cover of an uninspiring issue of The New Yorker. I was on the first floor, looking into the mirrors at an angle so exact I could see copies of myself down the length of them. If I peered down a certain way, it looked as if there was an army of my clones looking back at me. I still felt the sharp pain along the right side of my scrotum and as I looked into the army of me, I started to wonder if all of them felt what I felt, however unlikely. To them I was like some defective copy, which was actually a feeling I had been immersed in when I had met Miranda.

At the time, I held an online editorial internship at a small independent press. Since it was online, my office was wherever I wanted it to be: corners of Starbucks, a bench not too far from the lake that eventually dried up, my mom’s living room sofa. I would read PDF files of manuscripts and revert back to my editor with any revision suggestions, suggestions that were usually ignored. None of it felt like work at all, but through those endless chains of emails with my editor or with the author I was working with, I felt like someone else — someone better, someone smarter. And when that internship ended, I was never able to regain that persona that I put on through a screen, not even for Miranda on our first date. I wondered if a similar situation was occurring in Miranda’s ballet studio apartment with my face pressed close against a full-length mirror with copies of my better self reflected, infinitely looking back at the injured me. After a while, my nose smudged the mirror and my vision was blurred by the fog of my breath.

“Hey,” Miranda called down. “You want some of this?”

I could smell the smoke of the freshly lit joint and declined.

Miranda sauntered down the steel steps, wearing only a red t-shirt, white cotton underwear, and striped pink and yellow socks. She approached with such a sexy calm that I almost forgot that I was in pain. I left behind the army of me in the mirror to turn and be present. It was a perfect time to be enveloped in Miranda’s goodness. In times of uncertainty, in times of rich anxiety and worry, there was nothing that cured my ailments more so than Miranda. But, it has been so long since our last time, it was like I was craving her and the subtle drips of seduction like a strong kiss here or playful grab there was not enough to quench my thirst. There, with her strutting towards me, I felt the pain of panic both physically and mentally. It was like I had forgotten how to drink. I limped towards her to be saved.

We kissed and kept kissing. Our bodies pressed against one another in an eager unison. My arms wrapped around her waist and hers around my neck. I traced the slope of her back into the rise of her hips and pulled her into me. We fell back onto the chaise lounge chair. She was astride me, leaning over me. She lifted her t-shirt off above her shoulders and started to rock back and forth slowly. And then, pain.

“What’s wrong?” She said, breathing heavily.

“It’s my—”

Miranda rolled off me and looked at me with concern. Inadequacy was always a fear in the back of a man’s mind, or maybe just mine. Perhaps it’s not inadequacy, as in not being good enough, that worry men, but rather the act of performing itself was too much to bear. There’s another synonym for pretending, performing, as if I wasn’t really trying to make love to my girlfriend, as if I wasn’t actually trying to please her, but I was simply acting. And as the actor, who had minimal training in being able to put on a front as someone who knew which exact inch of skin to touch, which way to tease and fulfill, and balance giving and taking, letting their primal need subside to hers, I was deeply immersed in stage fright. Some performance. Maybe that’s why sex is so hard to portray in movies and in literature, because it’s not real, it’s not in the act. It is only a reproduction, yet another copy of something real and flawed, like mirrors or online personas of something better. The only way to fully experience sex is to be in the act. If only I could tell that to my fifteen year old self. But as a twenty-five year old man, who was in excruciating pain at the time of performance, the only thing to do was to try to please. As they say, the show must go on — maybe acting and entertaining were one in the same, just not when it came to sex.

After explaining the pain, I immediately started getting mother-like sympathy from Miranda. It was impossible to put into words the feeling of being tended to like some little boy, all while still being turned on, still wanting Miranda and feeling her hands on me, stroking, while she was naked and stunning as ever. How different her hair looked. Maybe it was the light or the way I perceived it through the half squinted blur of pain, but her hair looked amber, tied up in a messy bun. I wished I could just blurt out how beautiful she looked, but was that not just romantic sap that would certainly kill the mood, if a flaccid pain inducing hand-job hadn’t already?

Miranda gave up trying to get me off. I writhed in pain. All I felt was an electric shock running its course up and down from hip to testicle. Miranda put on her shirt and helped me off the lounge chair. She mentioned something about going to a hospital. I nodded in agreement with fluttering eyes. She muttered something about insurance. I passed out in her passenger’s seat, a pop song on the radio.

Sue Grimes was the one with cold scaly hands. They smelled of cigarette smoke and resembled death, much like the cigarette itself. As a former smoker I know the way the tobacco residue gunks in the crevices of your nails, introducing itself as a mustard tipped handshake. Sue Grimes, the Resident Nurse at OakMoore Emergency Department, looked and smelled the part. She took my vitals in the waiting room. I felt exposed as I watched the mother and teenage boy who sat together watching a rerun of Law and Order. Were not all Law and Order episodes reruns? With every episode came a strange Deja vu, a feeling that one had seen the episode before.

Had I seen this waiting room before? It held the usual dense air of sickness, the hum of a floor cleaner or perhaps an air conditioner, or some other machinery that only runs overnight. Hospitals buzz overnight. It was all so familiar. There was the mother and son, and yet I couldn’t tell who was the patient. My guess was the son. Did it matter? If that was the case, then the mother was not well, either — stress, worry, or what have you consuming her as well. Next to me, Miranda seemed stiff, biting the lip of a Styrofoam cup that was filled with ice. Her face showed no indication of her thoughts. I wondered, is empathy contagious?

Then, there was the girl — the young adolescent who sat directly in front of me with a tablet hiding her face. I had the strange feeling that she was taking pictures of me or perhaps of Miranda and me, especially when Sue Grimes and her cold hands placed some sort of electrical shock pads at two locations on my chest. That seemed pretty photo worthy, or sharable. Because of social media the world was still a place for you to offer things. I had a Facebook account for three months and never posted. I felt invisible. Picture this: the girl looking at me through the tablet, seeing a filtered version of me, while I sat and watched an episode of Law and Order, that I had or hadn’t seen, all while cringing at coldness and trying to describe the unknown carving of testicular pain to a woman in scrubs who just smoked a cigarette in the rain. There was a hashtag in there, somewhere. I dozed off trying to find it.

I awoke in a room where a Vietnamese or Filipino nurse introduced me to another Vietnamese or Filipino nurse. The new nurse was short and round and had the type of beauty that was made to be plastered all over social media profiles: shining lip gloss, tattoos, skimpy clothing, and various angles of her breasts. She was wearing a low hanging V-neck scrub top of a different color than the previous nurse, meaning she held a different position within the hospital. I once worked security in a hospital. Green scrubs were for surgeons, maroon for Patient techs, and black for resident nurse. What did Gingerbread Men scrubs mean? Especially in June? I sat in my wheelchair in my ill-fitting gown and listened to the two nurses talk, in what I guessed was Filipino.

The first nurse drifted away and left with me with the newer one who introduced herself as Luna, the ultrasound tech. To think that Luna had a different history of studies than the previous nurse, relaxed me a bit. It was as if I kept getting passed around to better hands. At least, that was what I hoped.

Luna directed me to lie down on a table much like the ones I ate lunch on in grammar school, thick high-pressure laminate tabletops with benches made of either particleboard or plywood. The thing that set apart afternoons of chocolate milk cartons and packets of carrots from my current adult self was a cold sheet of wax paper.

“All right, Papa,” she said. “Let’s get started.”

Few sensations ever align with others. Some are so unique, they can only be described as moments of a lifetime. Scoring a touchdown or hitting a homerun in the big game. An orgasm. Skydiving. All unique feelings that could only be felt in those situations. Nothing in my life has ever, or possibly will ever, align with the sensation of feeling the ice cold gel of the ultrasound wand rolling over the cusp of my right testicle in an aggressive manner. Not only did it hurt like hell, it was semi-erotic, and shamefully so.

One would think a certain gentleness would be taught, or even a shred of common sense would be had, that when dealing with that level of sensitivity, some caution or even some reserve was in order. For Luna, who kept steady eye contact on a blue lit screen and blindly ran the gel covered tool around as if she were an infant trying to jam a cylindrical piece of wood into a triangular hole, tenderness was not an option. What made it worse, was the small talk.

“So, you like sports?”

“How about this drought? My cousin Ricky said no corn this year.”

Luna was sweet, but her hands were cruel. There was constant friction and shuffling at play between my legs. I would cringe and squint, all while trying to think of Miranda, who was probably asleep in the waiting room. Is the definition of strength not to act normal in abnormal situations, or is that courage? How does one act normal when sprawled in a way that is tortuous; legs open, manhood exposed to a Filipino woman with large breasts and heavy hands? Even to think of Miranda didn’t help. When I pictured her, I saw her sitting there in the waiting room watching Law & Order. She felt so far from me, removed from the pain I was experiencing and far from the realization that something was wrong with me, or going wrong with me. It terrified me to realize that I was alone on the examination table, waiting and looking into Luna’s eyes for any change, any sign that something showed up on the screen that would suggest what was wrong. And if she found something, that meant something in me was defective, a proverbial finger to point, that something that was not only affecting me, but Miranda as well.

Minutes felt like hours. Luna clicked and typed, staring at her blue screen that showed a distorted image of, when zoomed out to a great distance, me. The screen showed a microscopic angle of my flaws in ways that I hoped were not cancerous or terminal, and also in a way that I have never seen before. To be reduced down to a graph, to numbers, seemed wrong and unnatural. I had once read an article about the possibility of having your soul scanned into a computer when you die. Someway, that something, somehow stretches your DNA makeup into binary code, each individualistic character of you being assigned a number. Your likes, dislikes, your flaws, your dreams, your desires, your insecurities, your passions: all translating to numbers on a scale. This made me think of technology as a religion. Lying there, staring at the glow of an orange light overhead, I had visions of internet-based heavens and hells with ultrasounds being the middle ground between the two. I must have dozed off trying to determine the fate of my soul. Yet, at the end of the examination, when Luna nudged me awake and directed me to clean myself off and throw away the six towels that were used, along with the crisp paper sheet that went soggy from sweat, the feeling that I felt could only be described as soulless.

Leaving the emergency room, filled with anxiety from all of the ultrasound’s unanswered questions, I saw the girl with the tablet once more. She was sitting on the linoleum tiled floor with her face pressed closely against the glass of a vending machine. She was begging her mother for a candy bar. Her mother was hunched over, still draped in a hospital gown, shivering.

“All right, all right,” the woman said, “just don’t tell your father.”

This innocent exchange of secrecy made me feel a little better. It invited thoughts of secrets that my dad and I had shared through the years. “You better not let your mother find out,” he said when he caught me smoking a cigarette under the awning of our porch. He lit one too. “She’ll flip.”

I smiled at the girl who was getting what she wanted and held Miranda’s hand as we walked towards the exit.

Outside, in the humid air of a summer night, I heard a breeze cut through the trees. I heard cars whooshing by as we walked down Easton Avenue towards Miranda’s car. I smelled burning wood and felt a coldness drift in. It looked as if it was going to rain.

“How you feeling, champ?” Miranda asked.

“Like I want a cigarette,” I said.

“Three days since you quit, and you’re already in the ER. At this pace, soon you’ll be over there,” she said, cackling, pointing to the cemetery across the street.

We drove off in Miranda’s Honda Civic with the radio off. High on a cocktail of pain meds, I was drifting in and out of a dream-like state, one where the words Miranda said would blanket me with comfort. There are words when said out loud that cause a physical reaction in the body. For instance, when tracking your heart rate on a smartwatch, a graph appears on the face of the watch that shows the beats per minute, or BPM. Some people distrust the watches ability to be directly in sync with the heart, but no current lawsuit has been settled. Regardless of the technicalities, it has been proven (by extensive research by Miranda and me) that there is a spike in the BPM when certain words are heard.

“I love you,” Miranda had said on a bright Sunday morning. We were hung over, slung across the wooden floor of her apartment where hundreds have danced, eating peanut butter from the jar with a spoon.

“Any reaction?” She asked.

“Increased by eight beats.”

We let a moment pass then tried again.

“I fucking hate you,” she said. “Anything?”

“Eleven beats.”

“I guess it’s true, hate is the stronger emotion.”

“Eh. Maybe the increase was from you saying ‘fuck’ also, and not just hate.”

A few minutes passed in silence.

“Let’s fuck,” she said,

“No change.”

She led me up to her loft, where, after twenty-two minutes, we were able to increase my BPM by thirty-three beats. “That has to be some record,” I said, gasping beside her, grazing her collarbone with a soft finger. She was trying to catch her breath. She checked her smart watch.

“I’m dead.”

Her heart rate monitor had flatlined, and then read an error message.

There in the car, on the way home from the hospital Miranda had said words like, “cancer,” and “tumor,” and “benign.” Subtly, I kept checking my heart rate via my smartwatch, constantly checking the watch to look for any change in BPM, but when she said “cancer,” and “tumor,” and “benign,” there was no change. Instead, I was joyed by remembering the innocence of our time together. What I would do to go back to that moment on Miranda’s apartment floor. I was focused on Miranda driving and wondering if we could ever get back there. She leaned over to click on the radio then held my hand. Over a pop song, I misheard Miranda say, “Hopefully, it’s binary,” when I think she meant benign. To hope whatever was slicing at my testicle was binary, a set of numbers punched into my body’s system, was to assume that somewhere this was all relevant to something. With Miranda feeling close to me again, I thought maybe it was.

I sat back, feeling like a copy of an illness, as if I was three-dimensionally printed and placed in a car traveling at thirty-seven miles per hour, or what the LED center console told us was thirty-seven miles per hour. I wondered if we were really traveling that fast at all, I felt so still. The street lights blurred past in streaks of white. Rain drops spotted my passenger-side window. It was getting harder to stay in the same position, the pain still slicing through me. Miranda, hand in mine, was focused on the road, still in the brown hoodie she wore hiking, her hair up in a lovely mess

“You look beautiful,” I said.

“Look,” she said. “It’s starting to rain.”

Nicholas Farriella is from Bridgewater, New Jersey. His work has been featured on Unsolicited Press’s Buzz Page and accepted by Riding Light Review. He works as a copywriter and Nicholson Baker follows him on Twitter.