Across The Margin / ATM Publishing presents the Epilogue of Arthur Hoyle’s The Jealous Muse, The Bargain with the Muse…

The Jealous Muse, Epilogue : The Bargain with the Muse

What do the varied life stories of these artists tell us about the terms of engagement with the muse? What does the muse demand from her supplicants? What does she give them in return?

In the arts, there are no guarantees of success, either artistic or financial, but the career paths followed here show that success in any form does not come without unswerving dedication and unhesitating commitment. The artist must place service to the muse above all other commitments if he or she hopes to master a medium. From the earliest years of her childhood, the keyboard was the center of Nina Simone’s life. She practiced for hours each day, foregoing the simpler pleasures of playmates. As a young woman, she pursued her formal training with a single-minded devotion to her aim of becoming a classical pianist, to the exclusion of personal relationships. Weston was in love with his camera, preferring it to all other companions. It was his means of mediating with reality. Cummings lived to write and paint, and deliberately kept himself ineffectual at doing anything else. And Matisse famously said to the woman he was about to marry, “Mademoiselle, I love you dearly. But I shall always love painting more.” The muse insists on uncompromised devotion.

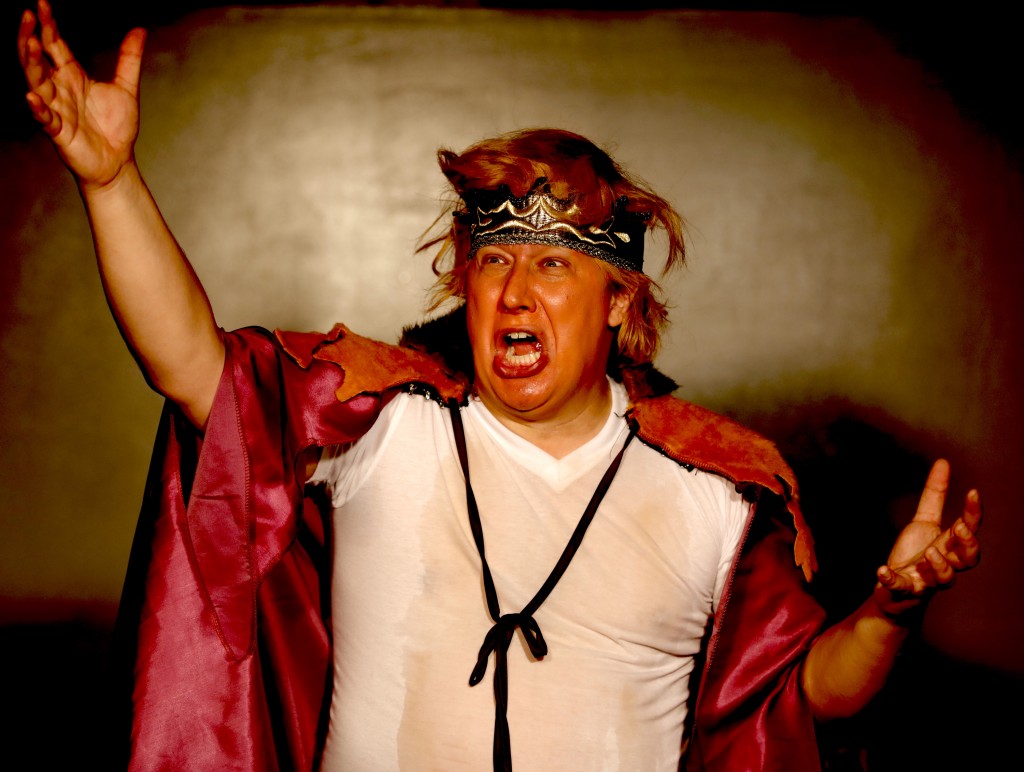

Talent is also needed, and often reveals itself early. This is the muse beckoning. As a child, Anjelica Huston amused herself and her father’s famous houseguests by inventing characters, costuming them, and performing them. Oldenburg, when still a boy, invented a fantasy world that he populated with real objects, anticipating the environments he would create over the course of his long professional career. The teenage Weston thrilled at the sight of the first prints yielded from his box camera and felt his life changed. Matisse found himself as a young man with the box of colors his mother gave him in his sick bed.

The muse requires helpers, and they usually come in the form of family members and friends. Matisse and Cummings were both supported financially by their fathers at the start of their careers, and in Cummings’s case, the support continued long after he was established as a poet. Anjelica Huston, raised in a theatrical family, was given her first acting job by her father, whose standing in the motion picture industry gave her access to roles. Maria Tallchief’s mother charted a course in ballet for both her daughters and sought out teachers of the highest professional quality for them. Weston was helped by his sister and his wife. Throughout his career, Matisse relied on his wife and daughter to pose, to assist in his studio, and to manage his business affairs. Not all family support was selfless. Nina Simone’s mother attempted to appropriate her daughter’s talent and put it in the service of her own mission as an itinerant minister. This pattern of being used by others was repeated by her husbands and became a source of profound resentment in Simone.

Friends also come to the aid of the muse. Cummings found patrons in two of his college classmates. Two white women in Simone’s hometown subsidized the child’s piano lessons and high school education, and raised money for her continued education in New York. And support sometimes comes from institutional patrons, like Weston’s Guggenheim Fellowships and Cummings’s Ford Foundation grant. Not all art, even of high quality, sells.

The demands of the muse, the sacrifices that she exacts, often have two severe and related psychological consequences—loneliness and self-centeredness. Mastering an art form, whether it is music, or poetry, or painting, or sculpture, requires years of solitary practice. Performing artists, dancers and actors, hone their crafts in social circumstances, working with other performers, but still must develop a singular artistic personality that distinguishes them from everyone else.

Nina Simone was acutely aware of the loneliness that accompanied her dedication to the piano. Her aim to become a black female classical pianist exacerbated her sense of isolation. Her loneliness made her vulnerable, susceptible to the designs of others who wanted to use her talent to further their own aims. She did not often enjoy her own talent and regarded it as a burden that had kept her from happiness. She was angry with her muse.

Matisse also suffered from his sense of isolation, not only from bourgeois French society, but also from many of his fellow artists. His isolation resulted from the restless innovation that drove his work. In continually seeking new forms of expression, Matisse distinguished himself, creating an art that was unique and groundbreaking. This was the mark of his greatness as an artist, but he paid a heavy price for it in frequent bouts of anxiety and insomnia brought on by self-doubt. He also had to fortify himself against misunderstanding and ridicule from the art public.

The self-centeredness of artists, their susceptibility to narcissism, is often remarked. Weston, in his journal, forcibly justified putting his own needs before all other considerations. His art was a higher calling. Cummings refused to develop a sense of responsibility to others, most especially his own daughter, because he feared doing so would take him away from his muse. This self-centeredness compensates for the loneliness that the artist experiences. The uniqueness of the individuality that the artist forms through complete dedication to a craft makes finding common ground with others difficult. Might the artist’s devotion to and love for his muse be a form of self-love?

Loneliness and self-centeredness give rise to other problems that beset many artists. Chief among these is difficulty forming and sustaining intimate personal relationships. Actors and actresses are especially noteworthy for the transience of their relationships, changing romantic partners almost as frequently as they change roles. The serial affairs and multiple marriages of Weston, Tallchief, Balanchine, Anjelica Huston, Cummings, and Simone are a sign that artists’ primary loyalty is to their muse, which is to say to themselves. Healthy relationships result from other-centeredness, not self-centeredness. Tallchief in her autobiography admitted that her marriage to Balanchine was based not on personal attraction, but on their mutual dedication to dance. Balanchine’s numerous marriages appear to be his attempt to live with an embodiment of his muse. He shed romantic partners in the same way that Matisse went through models.

Little is known about Matisse’s personal relationship with the young women who posed naked for him. We do know from his own words that the sexual energy stirred in him by the presence of the model fueled his art. If Amélie was not physically betrayed, she certainly felt emotionally betrayed by her husband’s attachment to his models. Their long marriage ultimately collapsed under the weight of Matisse’s self-centered priorities.

Scattered throughout the stories of artists are numerous symptoms of unhappiness: alcoholism, drug use, scandal, criminal behavior, depression, suicide. But Matisse once said, “One wouldn’t paint if one were happy.” (Hobhouse, p. 100) So perhaps for some artists attachment to the muse is not a cause of suffering, but a release from it.

Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen are rarely mentioned in this epilogue. They led private lives, and there is very little on the record about their personal relationship outside their work—their home life, their parenting roles, their personalities. I sought an interview with Oldenburg for this book, hoping to probe him about his marriage and how it blended with his artistic partnership with his wife, but was politely turned down.

But theirs seems to have been a rare and fruitful collaboration, bringing each of them both artistic and personal satisfaction. Though the public may think of Oldenburg as the artist, he took considerable pains to position van Bruggen as his full artistic partner, bringing to their work a dimension that he would not have found on his own. Their marriage lasted thirty years, ending only with van Bruggen’s death, and they created together over forty highly regarded public monuments located in Europe and the United States. Perhaps they found the same space together as Will and Ariel Durant, renewing with each new project not only their own creative sources, but also their personal relationship. They appear to have tamed the muse and made her their servant, not their master.

What then does the muse give her acolytes in exchange for their long dedication, their hard work, their skill, their personal torments and disappointments? Some, not many, achieve fame and wealth. Some only fame, and often not in their own lifetimes. But a great many artists labor anonymously, without reward or recognition, living in dire poverty or supporting themselves with simple labor. Raymond Carver worked as a janitor. Charles Bukowski was employed by the US Postal Service as a mail carrier. Henry Miller begged and borrowed. Van Gogh died without ever selling a painting. There are probably hundreds more examples.

What the muse gives all her devotees is beauty, a transcendent gift that transports them, and their audiences, to a higher reality. This was the declared aim of Matisse through his painting, and it is what the viewer experiences watching Tallchief dance as the Firebird, or Anjelica Huston become Maerose, or what the spectator feels while standing beneath a sculpture by Oldenburg/van Bruggen, or listening to Nina Simone as she sings “Wild is the Wind,” or reading “all in green went my love riding” by Cummings, or studying a photograph of a pepper by Weston. Like the goddess that inspires them, these men and women are not without flaws. But the muse transforms them into angels of light and understanding who make the soul visible to others. And this is why, more than politicians, or businessmen, or scientists, or athletes, or even priests, we revere them and hold them in our highest esteem.

Arthur Hoyle (www.arthurhoyle.com) is the author of The Unknown Henry Miller: A Seeker in Big Sur and Mavericks, Mystics, and Misfits: Americans Against the Grain. He reviews biography for the New York Journal of Books. His Substack newsletter Off the Cuff offers periodic commentary on the American cultural scene. Subscribe at https://arthurhoyle.substack.

Great stuff, Arthur