A short story which acts as an ode to the bountiful ways in which communities might congregate…

by: Ronald Tobey

It is a fine autumn day. Not “fine” in the way Oliver Hardy admonished Stan Laurel: “Here’s another fine mess you’ve gotten me into.” More like “fine” as in an heirloom comb, with an oyster shell handle and delicate tines you use in a ceremonial hopeful combing before going to a party.

I hear about the bull’s arrival from my farming neighbor who raises cattle and dogs. She calls me late in the morning when I’m working in our horse barn.

“A bull coming your way”, she says breathlessly. “You’ve been chasing it, I guess.”

“Where?”

“It walked up our driveway. Now it’s walking into the woods and heading up the alley toward your barn.”

I run outside and look down Oak Alley, as we call the tractor road connecting the barn campus to several fenced fields. An Angus bull on short legs strides as if it knows where it is going, toward me.

From a distance I guess it weighs about 1500 pounds. A small bull, but not inconsiderable, one preferred by farmers who are concerned a large bull might injure their cows when mounting them while breeding.

I get out of its way, fearing it might charge me, but it doesn’t. It continues a slow steady pace up the driveway toward our log cabin. I run into the barn and get a bucket of sweet feed to lure him. But, where is the question? I hope to have an answer in the next several minutes.

The bull walks around the slope end of our attached garage. When I catch up with him, he is standing still, facing into the woods surrounding our home. He appears to have no planned destination.

I give him a wide berth, walk around him, shake the feed in the bucket. He turns his head toward me. I walk around the front porch of the house and he follows. I lead him back to the driveway and into the double gate to a hillside field in front of our house. As he enters, I run fifty feet to close the inner gate and then around him to close the entry gate. He’s penned in. I nervously eye the eight-strand wire fence, recalling when I chose eight strands with a solar charger, now running at only 2.3kv. I never thought I might need to confine a bull. He stands still as if he had drunk a barrel of home brew, not testing the wire. Did he expect to be picked up? Can bulls expect anything?

By this time, my wife comes out of the house. “I don’t know who to call. Maybe it escaped from the nearby slaughterhouse fields.” She suggests calling the facility.

A woman answers, we do not realize she is a near neighbor. She says, in an accent I barely decipher, “I know who to call. I’ll take care of it,” and quickly hangs up.

Thirty minutes later, a Ford 350 dually pulling a livestock trailer is driven up our hillside driveway. The driver is an older man, who introduces himself. He owns the slaughterhouse. Then an old pickup truck follows up the driveway. A heavy-set man with a large unkempt gray beard and long gray hair, in dirty farm overalls, steps out. The slaughterhouse owner introduces him as Jud. “His bull,” he says. I am told later, this old farmer works in the slaughterhouse. Has worked there since high school. He lives nearby in a ramshackle cottage with a half dozen old inoperable autos and rusting farm implements parked in front, along the state highway. A patchwork of cattle fields with haphazard electric wire fences fill the shallow land behind his humble dwelling. Later, I am told, he is divorced, has three sons. I meet two of them when they roar up to our group in a 4×4 all-terrain vehicle. The boys are all over six feet tall, heavy-set, in their twenties and live in the cottage by their father’s house.

Next to arrive is my farm neighbor who called me earlier, stopping by to see what’s going on. We are a party of seven, convened to return a bull to its farm. She sees Jud, takes me aside, and tells me a story. She was here several years after moving in with her new husband before she met Jud. He shows up one evening, having imbibed enough beer to get up the courage to introduce himself, by driving to their farmhouse and, unannounced, knocks on the door and invites himself in. A shy and quiet man.

“Will this fence hold the bull?” the slaughterhouse owner asks.

“I hope so,” replying earnestly. My wife and I, being newly relocated to this rural corner of West Virginia, are never sure when curt factuality is expected politeness, or if nervous hyperbole is required in a situation.

The truck and trailer are re-oriented by driving around our barn, then the trailer is backed to the captive bull’s pen. The trailer rear gate is opened. A gap of four feet exists between the gate to let the bull out and the trailer. I confess, “I’m worried the bull will just escape through the gap.”

The slaughterhouse owner, who apparently has hauled this animal before, says, reassuringly, “He’ll just walk in.” And the bull does.

I am relieved. Someone makes a joke. There is laughter. Fences are expensive and require constant maintenance, so cattle often escape. Capturing escaped cattle, Sunday church services, and annual voting at Little Creek Church community hall are how this community meets. I realize I am happy. It’s a fine feeling.

Ron Tobey grew up in north New Hampshire, USA, and attended the University of New Hampshire, Durham. He and his wife live in West Virginia, where they raise cattle and keep goats and horses. He is an imagist poet, expressing experiences and moods in concrete descriptions in haiku, lyrical poetry storytelling, recorded poetry, and in filmic interpretation. He occasionally uses the pseudonym, Turin Shroudedindoubt, for literary and artistic work. Ron is active on Twitter, his handle is @Turin54024117.

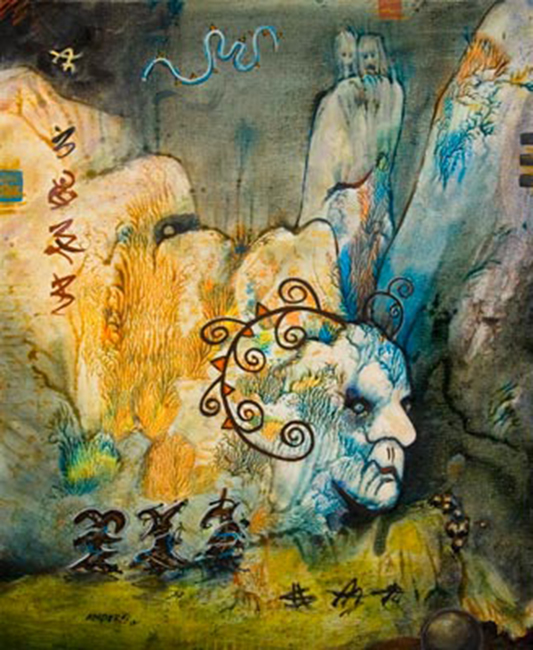

Header art by John Henne.