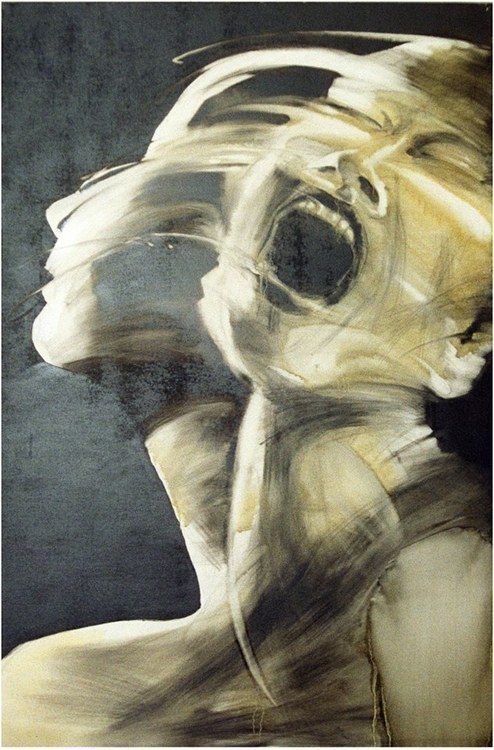

“There is love bound up in my decision. Do not fear. All will happen as it is supposed to.” A fetching work of fiction with an extraordinary woman at its core, whose allure acts as a fulcrum driving all that unfolds…

by: Chris Cleary

July 2, 1826

My name is Georges Washington Fournier. I was born in Watsanachu on the banks of Pennsylvania’s Schuylkill River, on the final day of the last century. My name honors our illustrious first president — God bless his memory! — who died some weeks before I was born. My father, at one time a most optimistic Girondist but disillusioned by daily bloodshed, fled the horrors of Paris for the safety of American shores, thus the Frenchified version of my name.

This account does not concern me, however, but my sister, younger than me by four years. She is Sophonisba Silverwood by way of recent marriage, and a sweeter name one could not design, altho’ as Sophonisba is rather difficult for me to say, I have always preferred to call her Sophie. She is now confined to her birthing bed and any day shall bring into this world my nephew or niece. She labors in the throes of a delirium and swears she will not survive the upcoming ordeal. Therefore, she has ordered me to commit to paper certain events throughout her short and unhappy life.

Until recently, we were part of a family poor but industrious, living down by the canal, above a tailor’s shop established by my great-grandfather Isaac Houghton. Subsequent to his death, the shop had become Houghton and Fournier, with my Uncle Harry living hard by with his Portuguese wife and five children. Besides her brother, my mother has two sisters, one of whom, my Aunt Judith, lives in the Boro of Rocks with her husband, Twomey, the confectioner, and their four children. And so you see that Sophie and I had easily at hand a vast array of playfellows from which to choose.

Once a month my family with my Houghton cousins would make the ascent from lower Watsanachu up to the Ridge to visit the Twomeys. Their modest house afforded not much space for the number of tempestuous children, but it was situated across from a clearing that was part of the cemetery of St. Timothy’s. There the parents would watch us romp together at Scotch-hoppers, or separately, the boys with their bilbo catchers and the girls with their jeu des Graces.

Cousin Patrick, the eldest of the Twomey children, fancied himself a host in the theater of life. One day he gathered up the largest chestnut hulls he could find. He then sat us down and, placing a pebble beneath one of the hulls while our heads were turned, challenged us to guess under which of the three it was hidden.

I told him that was not the way to proceed, that he must let us watch him hide the pebble and then shuffle the hulls so quickly as to confuse us to its location. I might have added that there was often an element of deception in the game, but his audience was comprised of younger children, and so I let matters be. The children took turns guessing, and as you might expect, their answers being based on nothing but luck, they were correct but once out of every three ventures.

Sophie was by herself around the other side of the tree, attempting to fashion a small doll from twigs and twine, yet giving Patrick’s game part of her attention. I called my sister over to take her turn lest she begin to feel isolated from our group.

“Cousin Sophie, might you find the pebble hidden beneath?” Patrick asked.

I reminded him to show her the pebble first and then move the hulls about, and rather slowly at that, to make it easier for her to decide.

She darted me a look with her green eyes. I must mention now that I have it in mind that she already had the most beautiful, the most captivating eyes — not just green, but a deep jade, set off by dark brows, tho’ the rest of her hair was ringlets of gold.

“Do not call me a fool, brother mine! This is not a mere game but an occasion for hypothesis.”

I was not aware she knew such a word. I scarcely knew what she meant and laughed at what I thought was pretense.

“Hypothesis, eh? What kind of philosopher do you think you are?”

“I have been listening to your silliness, so let me attempt to enlighten you. You ask under which hull the pebble sits. I will surprise you. It is under all three!”

“What!” Patrick cried, and the other children giggled.

“She is thinking about the kind of game that involves wager,” I said. “Only the answer in that case should be None. The gambler will always lose because the pebble is hidden in the mountebank’s fist.”

Sophie regarded me with disdain.

“From where I stand, there is an equal chance of the pebble being hidden there, there, and there. Because I have not seen it yet, it is correct for me to say it is now under all three. Only when the hulls are lifted and I make my observation can there be only one answer.”

Even from such a young age, my sister has always been able to amaze me.

I have already written that our families did not to any significant degree distinguish themselves from others that dwelt on the thoroughfare that ran through the heart of Watsanachu. We were, like them, honest laborers that worked constantly to keep one pace or two out of the grip of debt. That is, until recently, for in the autumn of 1821, all of our lives were suddenly transformed. The change began with the death of my Great Aunt Beatrice, the spinster sister of my mother’s late father. Almost immediately after she was laid to rest next to old Isaac in the churchyard of St. Timothy’s, Uncle Harry, unusually distraught as if he had lost his own mother, disappeared for several days. During his absence, my father would utter a string of fine French curses about having to uphold the business by himself. But my Mother calmed his ire with assurances that Uncle Harry had legitimate cause for his temporary withdrawal from our lives and would return in good time, which he did, but still shaken and despondent.

And then, come Christmas, Uncle Harry was made marvelous rich. A coach drove up to the door of the shop and three heavy chests were unloaded onto the floor. Uncle Harry unlocked the first chest and broke the seal. Neatly arranged inside were stacks of bank bills, bonds, and some coin. So too were the second and third chests.

“Mon Dieu! Incroyable!” my father exclaimed.

Uncle Harry fainted dead away.

He never received an explanation for the wonderful magnanimity shown him, at least none I was aware of. The identity of his benefactor remained a mystery, though I am sure the answer lies somewhere. It is enough now to say that all our lives were suddenly altered. The contents of just one chest being more than enough to secure the comfort of his immediate family, Uncle Harry, generous soul that he is, shared his blessing with the Fourniers and Twomeys. He and father remained in their trades, but could now afford to relocate the shop to a fashionable section on the Ridge, hire a number of skilled workers, and begin to service a more affluent clientele.

As our status rose, so too our domestic situation, up the steep hill away from the wharves and canal. Father took a house on the corner of Lyceum Boulevard and Peach Lane. The Twomeys moved to the fancier western side of St. Timothy’s. Uncle Harry purchased a grand house on Green just below Mitchell’s Alley, tho’ Sophie confided in me that she thought him reluctant to put on such airs, and that he was merely acceding to the will of Aunt Clementina.

There are no roses in life but they do not present thorns, and a poor man suddenly made wealthy often loses his talent for self-governance. Almost immediately following the relocation of the shop, my father began to acquire the idle habit of gambling. This was most surprising since Father had always been a conscientious man of industry, but now that his poverty was no longer of concern, he found he took pleasure on the mere chance of the card table. It seemed a harmless diversion at first, but in short time the vice grew beyond his control.

My sister was also quite affected by the change in our situation. Her blossoming into young womanhood at this time, a transformation of character would have fallen upon her regardless, but our wealth threw a light upon her, in the sight of both the bachelors of Watsanachu and her own regard. Those eyes of jade, framed by her dark brows, leapt out from her fair complexion and enticed would-be suitors, and she embraced the power she came to have. She playfully poked at the line of propriety, much to my mother’s exasperation and mine. Invitations to events that we little dreamt of receiving as a humble tailor’s family now arrived at our door with regularity, and local rakes would never fail to fill her dance card. My good friend Wimpole, immune to her charms, kept me apprised of Sophie’s every indiscretion. There was one such rake, by the name of Mallory, who would take her for whirlwind excursions in his bright yellow barouche up and down Lyceum Boulevard, frightening the residents, who cast many a disapproving gaze.

I took Sophie aside one day and presumed to lecture her. Father was not to be found, and Mother, having already upbraided her, would surely have made the matter worse.

“It is not seemly,” I said, “and we are already looked upon by some who regard us as uncouth parvenus. Do not give them provocation.”

“Oh, what do I care for their censure? Do not be such a mouse.”

“Then think of the danger that you might place yourself in. You invite the wrong sorts of fellows. A serious attachment to any one of them would surely be a mistake.”

“You are such a sweet thing to care so, G. W., but do not suppose I am unaware of how I comport myself. I know these young cubs better than you think I do. If I perceive any of them to consider a serious attachment, as you put it, I merely peep under their shell, no matter how handsome a shell it is, and look down the years to discover what is revealed.”

“What do you mean?”

“Don’t you know? It is a simple exercise. My beaux line up to dance, and I take each one after the other, hand in hand — Mallory, then Bainbridge, then Baldwin, then Fleming — and there on the floor as the music beats time, look deep into them, and I picture what destiny I might share with each one. But be content — I have seen nothing yet that is desirable. So while I might toy with them in the present, they shall not toy with me in the future. I will reject them all. What I seek is not beneath any of them.”

“Oh, yes, I understand you! You speak of the moral character beneath.”

“No, not beneath. Beyond, more like. Oh, how can I explain it if you cannot do this too?”

Tho’ she did not mend her errant ways and continued to conduct herself with an unbecoming liberality, and tho’ my mother existed in a continual state of reprimand, Sophie did not meet with anything worse than the frigidity of our scandalized neighbors. Yet news of her behavior had spread as far as Shurston on the western limits of Philadelphia, to which my father sometimes would travel as the town featured a gaming house of local infamy called the Scarlet Tippet, and it was there that the twin evils of Uncle Harry’s benefaction intertwined.

I was not able to gauge the degree of my father’s intractable habit, as thank God it did not exist in cooperation with an indulgence in spirits or lewdness. So I learned of its toll quite abruptly one mild March afternoon in 1825 on the Ridge. I was with my friend Wimpole when I was accosted by a stranger in a long, black coat. By the menacing tread of his boots alone I supposed him a brigand, and yet there was much else about him to bring me to such a conclusion. His dirty, black hair hung to his shoulders, and his moustache drooped in the style of Jean Lafitte, whose portrait I had once seen sketched in print. His eyes asquint as he looked me over, he blocked my path and said, “You are the Fournier boy, are you not?”

I did not want to seem a coward in front of Wimpole, so I gathered nerve to reply, “I am hardly a boy. I am near 26, sir, and I am a gentleman.”

“I do not care about your age or your station. Tell your father he has not replied to my offer, and he is avoiding me. Tell him MacRitchie expects a timely answer.”

That night I told my father about the strange blackguard with the enigmatic message, and after dismissing me and my sister from the room, behind closed doors he broke into sobs before my mother. He confessed that he owed this MacRitchie a sizable debt, not enough to ruin us entirely, but enough for us to feel its sting. The money itself was not so much MacRitchie’s object as something else more sinister — he had heard certain gossip about Sophie. He might be willing to forgive the debt in its entirety if my father would permit him to call on her and, if he liked what he saw, to begin a courtship. I am sure he had put the bargain in much coarser language. A quarrel ensued at the card table, my father said, and had he not been hurried away into the street, he might have challenged the scoundrel to a duel on the spot.

“I will gather our assets and see what I can produce. I have been trying to raise the money at other houses, but I have fallen on hard luck there as well. I suppose I might ask Harry, but as it was his money to start —“

“Oh, François! How could you be so foolish! So foolish and so weak!”

“I have been a fool! I do confess it!”

My mother’s words words must have bitten deep into his soul, for the next week our family met with an unbearable tragedy. We learned from a man called Freeland, one whom he had befriended at the Scarlet Tippet, that my father had challenged MacRitchie to a duel and vowed to meet him in the early morning hours on the commons by the river below Shurston. Freeland, his second, reported that my father’s shot missed its mark, but that MacRitchie’s did not. My father died instantly. The whoreson MacRitchie fled immediately.

God rest his soul! I am compelled to break from these events to offer a eulogy, or at least to search among the impulses of his heart for explanation for his most hasty decision. But I have suffered in private and spent all my tears. Moreover, my sister’s tale is still not fully told, and ever onwards I must press.

It is fair to say that of us all, Sophie allowed her grief to master her the most, for she knew that our father forfeited his life protecting her honor. She became reclusive, beyond the normal dictates of mourning, and my mother and I rarely saw her for weeks after the funeral. She relinquished attendance at church. She relinquished family meals. And of course, she relinquished all her beaux, who soon counted her among the dead of Watsanachu.

That is, all but one, the young apothecary Andrew Silverwood, who in desperation for her well-being continued to send her his wishes, tho’ he received not one word in response. Silverwood was unlike the rest of her suitors, I am happy to say. A true gentleman, unassuming and contemplative, and most comfortable among the concoctions and curiosities of his scientific endeavors. Tho’ but one year my senior, he bore the countenance of a man much older. He had already grown bald but for thin wisps of red at the sides, and his lips would sometimes quaver as if he had the palsy. The determination of his affections eventually won out, and in the autumn of 1825, Sophie agreed to his calling upon her. I was not present at their initial discourse, but Sophie afterwards told me in private that she had given him encouragement.

“He is a good man, G. W., and I have looked down the years, in that manner of which we once spoke. He will wish nothing more than to please me, no matter how costly my request.”

“I am sure he loves you, Sister, but do you love him? A marriage must be founded on that most solid of rocks.”

She smiled at me. Her smile was not cheerful or mocking, as it had been of old, but melancholy. Nay, forlorn.

“There is love bound up in my decision. Do not fear. All will happen as it is supposed to. But the marriage must be soon. I told him we must marry soon.”

I asked her why, but she suddenly stood and dismissed herself.

The period of their engagement was unusually short. Wimpole said, and I was prone to agree, that her grief for father’s death was pressing upon her, and that only a special attachment, amorous or otherwise, would assuage it. The wedding ceremony was held at St. Timothy’s, and it was a relief to see my cousins gathered together as we had when we were younger. Uncle Harry, taciturn and appearing haggard, gave away Sophie at the altar. Tho’ he had offered to purchase them a small house, Sophie declined his generosity, claiming that she preferred to stay where she was. There were more than enough rooms to welcome her new husband under our roof. “Besides,” she said, “certain people already know where to find me.”

At least that was what I thought she said. Her observation was little more than a mumble.

Silverwood was a gracious brother-in-law, not keen at conversations after dinner, but always diligent in good relations with my mother, who was pleased with her daughter’s choice. Ofttimes it seemed to me we had in fact gained a manservant, he was so obliging to her needs.

All bode well for their domestic bliss, but then MacRitchie reappeared one night astride his horse on the boulevard outside our house. I had overheated myself by the fireside and stepped onto the porch for the chill of the late autumn air, or else I would have missed him. He seemed unworried by my appearance and waited outside for several seconds before his horse trotted away. He returned in the same manner and location the following two evenings.

I took Silverwood aside and informed him of MacRitchie’s baleful history with our family and the apparent renewal of his harassments.

Silverwood, usually so imperturbable, exploded in a fit of temper.

“I shall thrash him! Not to within an inch of his life, no, sir, but beyond! I shall make him pay dearly for what he has done!”

“No, Andrew,” I protested, “it is my office. He murdered my father, and so the duty falls to me. Tomorrow night he is sure to return, and in the meantime, I will secure a piece that shall knock him bloodied from his horse.”

“Neither of you will do such a thing.”

I had not noticed Sophie hidden in the folds of the curtains. She stepped from the window, from which she had been regarding MacRitchie’s ominous shadow on the boulevard.

“I will not hear of thrashings or pistols. He is a sizable man, Andrew, and will quickly turn the whip upon you. And, G. W., you are no marksman. Your hand will tremble so, you will end up just like father. Violence will not do. Now sit you both upon the sofa.”

We obeyed. Her jade eyes gleamed with cold retribution.

“Husband, you must be subtle. No doubt you have on the shelves in your shop some remedy for the situation. When he is distracted, put something in his cup that will wrack his body and stop his breath.”

Have I not already said that my sister has always amazed me?

The next day we three conspirators had much to do. Silverwood closed his apothecary and spent the day in preparation. Among the unusual items upon his backroom shelves were a series of bottles containing various extractions derived from certain almonds he had collected on his student travels to the Mediterranean. Sophie had arranged for her and her mother to dine at the Twomey house on the fateful night. This was moreover sufficient reason to allow the cook and the maid to leave early that afternoon.

Mine was a more strenuous duty. By the almighty hand of Providence we were at that time arranging for a marble memorial to my father to be installed at the center of the garden. As we waited for its completion, workers had dug a hole of significant size for its foundation. My Mother unawares, I dug a second hole within that first, a hole large enough to conceal a body.

Without fail, MacRitchie arrived at our gate the next evening. I summoned my courage and approached him with my arms outstretched lest he think I carried a pistol, but he appeared so haughty I do not think he would have worried much.

“It took you long enough to confront me,” he said.

“I know what you do here,” I replied, counterfeiting an air of submissiveness. “Your intent is to frighten us in order to collect the money that is still owed you by our Father. You have accomplished your goal. I will arrange for repayment.”

The villain shook his head slowly. “The money is no longer my sole concern. I am here also for access to your sister.”

Now my counterfeit was shock, tho’ I knew well enough his desires. My response was hushed.

“Sir, she is a married woman!”

“To some weak fool, as I have seen. That does not alter my demand. Why she would consent to him I cannot imagine. She is a vixen in her heart, and too much for him to handle. It is only a matter of time before she lapses in her vows, and it may as well be with me.”

I felt my face flush with indignation, but I maintained my pretense.

“As you say, he is a fool and she ungovernable. Reinstate your previous offer. If you were to let go by the debt, I can arrange for the two of you to meet. On Friday evening at 6:00 there will be nobody home but I. Visit me then and we shall discuss the particulars.”

On Friday evening, with Sophie and my unsuspecting mother away on the Ridge, I welcomed the devil into the sanctity of our house. At Sophie’s suggestion, Silverwood excused himself from the visit, feigning a mild headache, and stowed himself in a nearby room lest MacRitchie become violent.

I gestured for him to take a seat in the drawing room, but he insisted on pacing about the various rooms to appreciate our wealth, or at least that was his excuse. I knew he was checking for hidden accomplices, and so I joined him in his meanderings and described the furnishings loud enough for Silverwood to hear. Finally MacRitchie was content and made bold to seat himself at the head of the dining room table.

I laid out the procedure by which Sophie and I would deceive her husband and mother. It would become our habit to ride weekly to Lauriston for afternoon walks in their beautiful park. We were to meet him there for the exchange of one of Father’s IOU’s for time spent with my sister in a discreet rooming house nearby. When the tryst was completed, he would return Sophie to my care.

MacRitchie seemed to admire the simplicity of the plan.

“I have but a certain number of these notes, but who is not to say that by the time I run out of them she will already prefer me to her husband?”

“Then we have an understanding,” I replied, walking to the sideboard to pour two glasses of wine. “Let us drink to our mutual benefit.”

I handed him a glass but did not immediately drink mine. I watched his eyes watch me in return. He placed his glass upon the table before him.

“Do you think I am a fool?”

“What do you mean?”

I knew exactly what he meant. I had made certain that my body blocked his sight when I had poured the wine.

“Let us trade glasses then.”

“We shall do nothing of the sort! It is you who insults me! If you think I have tampered with your drink, then go dry or find another bottle!”

“I think I will. This will be my house one day, and I must get to know it better.”

He rose and strode to the kitchen.

“Very impressive,” he commented as I stood in the doorway watching him make inspection. “A well-stocked larder. Yes, I could easily live out my days here. Ah, here we are!”

He found the three or four bottles of wine that the cook kept at hand to avoid her repeating excursions to the wine cellar. He seized one, uncorked it, and raised it in a mock salute.

“To better acquaintance!”

“To better acquaintance,” I replied and smiled.

He drank and I smiled again.

“Would you care to see the gardens? If, as you say, you are to become master here one day, you will want to know the entire grounds.”

I figured I might save us the labor of having to drag his body there if he carried himself to his grave.

“No, I don’t care for your flowers. All I require is the comfort of a…”

He stopped abruptly and smacked his lips.

“Damn your wine! It is too bitter to enjoy!”

He raised the bottle to his nose and sniffed. He then turned his back upon me, set down the bottle, and chuckled.

“You arrogant whelp. You think you have got the better of me? Maybe you have. But if I am to go to hell, I will take you with me.”

He turned again to face me, reached beneath his coat, and withdrew a knife. My legs froze. I knew all I had to do was to offer him chase throughout the house until the poison began to work, but for some reason my spirit counted me as one already dead.

Suddenly the door to the wine cellar burst open. In my panic I had forgotten about Silverwood.

“Then you must take two of us!” he cried as he threw himself at MacRitchie.

I marveled for only a second about what a tiger Silverwood had become. His desire for revenge had completely transformed him. MacRitchie turned to wield his knife, but Silverwood picked up a chair as a shield to deflect the blade. I thought that an admirable maneuver and copied his example. This rather pitiful battle ensued for I know not how long, but I soon began to notice MacRitchie become dizzy and short of breath.

“That is about all for me,” he said, panting heavily and lowering his knife. “I know nothing of guilt…a waste of emotion…but you, Fournier…may your guilt haunt you for what you have done.”

His utterance actually stirred in me something like pity, even tho’ he had brought it all upon himself.

“That is about all for me,” he repeated and then glanced over Silverwood’s shoulder. “That is about all, but not all entirely.”

He then hurled himself at Silverwood, grabbed the legs of the chair, and used it to propel Silverwood backward and down the steps to the wine cellar. I heard him cry once as his body clumsily struck the rocks of the stairs. A series of short thumps told me his body had fallen the entire length.

MacRitchie had but a few seconds to regard his handiwork before his body began to convulse and an awful frothing issued from his lips. He fell to the floor and continued to writhe for several seconds before he lay still.

I descended to the cellar, but it was to no avail. Silverwood’s fall had proven fatal. Yet I had no time for tears. I dragged MacRitchie’s body to the garden, and with the poisoned wine, I buried him. I put the scene of the struggle to rights and waited for my sister and mother to return, ready with the falsehood that Silverwood, seeking a fresh bottle, had slipped and fallen to his death.

These were the sad events of 1825, and now it is the summer of the next year, and my sister is confined to her bed awaiting the birth of Silverwood’s heir.

July 3rd, 1826

I have shown her this account, finished in the early morning hours. She approves of its content but with the following addendum.

“Poor Silverwood!” she cried. “He might have lived still had I never accepted his proposal of marriage. Do you not see how it all falls out like a chain pulled from murky waters? One link revealed reveals another, and that link another, and so on. It is all a matter of peering below the surface and choosing which chain to pull.”

I recalled Patrick’s pebble beneath the chestnut hulls so many years ago, in the paradise of our childhood.

“To spare Mother and you from MacRitchie’s designs, I was forced to resort to an evil just as unforgivable. You see, G. W., I married the apothecary because I knew it would end thus!”

Chris Cleary is the author of four novels: The Vagaries of Butterflies, The Ring of Middletown, At the BrownBrink Eastward, and The Vitality of Illusion. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in the Virginia QuarterlyReview, The Broadkill Review, Gargoyle Magazine, Oddville Press, Across the Margin, Belle Ombre, Easy Street, North West Words, and other publications. His short fiction has been anthologized in the award-winningEverywhere Stories.