by: Christian Niedan

The first installment of a twelve part series, recounting and expanding upon an array of interviews with an assemblage of historians and history-infatuated filmmakers. We kick off the series with a deep dive into the prime of Constantine with an essay about the prolific public television work of UCLA history professor Eugen Weber…

From the 5th-10th Centuries, the “Dark Ages” of Western Civilization unleashed a tumultuous and bloody era upon Europe. The centuries that composed the fall of the Western Roman Empire and its caesars, the rise of the great Byzantine capital of Constantinople with its emperors, and the reign of legendary Frankish king Charlemagne are rife with cinematic potential. Sure enough, there are plenty of films about King Arthur, whose legend arose from Dark Ages’ England. Also, the History channel has aired multiple seasons of the Dark Ages-set series, Vikings, a saga that begins in 793 with the infamous raid on the English monastery of Lindisfarne. Yet, storytelling explorations of the period’s wider peoples and places seem to be mostly left to academic historians. Indeed, most Western wide-release film/television productions seem to chronicle the latter Middle Ages that begin with the Crusades era of the late 11th Century. The reason may be the very chaos that earned the era its nickname of “Dark.” This was a time before the film/TV-friendly era of shining knights and impressively towering castles that were spawned by Europe’s societal reorganization under Feudalism, beginning in the 9th Century. So, rather than screens, books have become the premiere way for interested audiences to relive the Dark Ages.

However, in 1989, UCLA history professor Eugen Weber brought the Dark Ages to American public television with The Western Tradition, a 52-part televised lecture series for PBS (via WGBH Boston, in association with The Metropolitan Museum of Art) filled with tales of the era’s greatest city and mightiest king. I was a history-obsessed middle school kid when I first came upon the series on New York City’s local PBS station, and remember being captivated by Weber’s direct-to-camera delivery and his impeccable pronunciations of every far-flung kingdom, ruler, and religion. I was also fascinated by the vast variety of ancient imagery appearing throughout the series, which were sourced by research teams at the Met and UCLA (where Weber joined the faculty in 1956). Finally, there was the atmospheric background score that accompanied the visuals, and helped quickly immerse me in a different time and place. This was more than some PowerPoint online history class, it was a multi-dimensional and easily-accessible screen production aimed at capturing even short attention spans. In 2014, to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the series, I revisited a few of its episodes via essays and I heavily quoted Weber’s lectures, including his evocative opening narration to Episode 15, “The Byzantine Empire”:

Eugen Weber: “They called it ‘The Second Rome.’ A great city astride Europe and Asia, and its vast empire — which would preserve Greco-Roman culture and transmit it to the West, when Rome itself lay in barbarian hands. The Byzantine Empire, this time on The Western Tradition…”

That great city was Constantinople — or, as Weber puts it, “what Paris was, what New York is today: the foremost city of luxury, fashion, and culture. Also, the city of sin, corruption, and material temptation.” It was named for the Roman emperor, Constantine, who made it the Eastern Roman Empire’s capital in 330, in large part due to its strategic location along the narrow Bosporus passage between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean. Weber highlights the irreplaceability of Constantine to the administrative mechanism of Byzantine state bureaucracy, by relating the following anecdote about what happened following his death in 337, when his heir was far from the capital:

Weber: “The embalmed remains of the dead emperor continued to rule the empire through a whole summer, and autumn, and winter — with couriers reading their messages before it, ministers making reports to it, and courtiers seeking audience before it.”

Though Constantine was the son of a future Roman co-Emperor, Byzantine rulers that followed him descended from remarkably diverse backgrounds. That was because whether by election, or birth, or by force, the only real qualification to rule the Byzantine Empire was to be a Greek Orthodox Christian. As Weber summarizes, the throne was open to pretty much any churchgoer, wealthy or poor, educated or illiterate:

Weber: “Leo I in the 5th Century had been a butcher. People in Constantinople used to point out the stall where he and his wife had sold meat. Justin I in the 6th Century was a poor swineherd from the countryside who first appeared in the capital with bare feet and a pack on his back. And then one day his nephew left the family village to join him. His name was Justinian, and he became emperor in 527…Phocas, who ruled in the 7th Century, was a simple centurion. Leo III in the 8th Century was an odd job man. Basil I in the 9th Century was a peasant, probably a shepherd from Macedonia. And Michael IV in the 11th Century was a servant from Paphlagonia on the Black Sea.”

However, that eclectic mix gained a throne with one hell of a caveat: the only way to unseat them was via successful coup — and Weber notes that there were a lot of those:

Weber: “Out of 88 emperors who ruled in Byzantium through 11 centuries, over 1/3 would be usurpers, and as many died in violent circumstances — poisoned, stabbed, strangled, beheaded, starved, tortured to death, or simply blinded, which was considered more humane.”

Yet, despite the high turnover rate, to be emperor elevated one high above other Byzantines, while also distancing oneself from those subjects, so as to prevent coups. This resulted in a bizarre royal protocol during the empire’s turbulent early centuries. As Weber describes it, “spectacular megalomaniac kind of drama is devised. Both to enhance power, and to make up for the shortcomings in this power.” That drama extended to audiences with barbarian leaders, with the goal of wowing them toward peace — as embodied by Weber’s vividly cinematic example of one tribal chieftain’s experience:

Weber: “He enters the octagonal room where this silent, stiff, completely motionless figure is seated on an elevated throne veiled by purple fabrics — purple being the imperial color, and forbidden to everybody else. The furniture of the room is very strange. There are golden lions, golden griffons, golden birds perched on golden trees, rather like a glorified kind of mechanical toy store gone wild. And all of this is set in motion by the chieftain’s entrance. The animals open their mouths, the birds open their beaks and sing, the griffons whistle, the lions roar and thrash their tails. And meanwhile, the visitor has to prostrate himself. And when he gets up, he cannot see either the emperor or the throne. Finally, he discovers that the throne has somehow risen way up, and the emperor is still sitting on it, stiff, painted — but now wearing another costume than the one he had apparently been wearing a moment before, and certainly too far away to hold a conversation. The man is not just impressed, he is befuddled. He is dominated by all this splendor.”

Domination was also an effective royal method in Europe’s western regions, where Frankish king Charlemagne (translated as Charles the Great) would build his Carolingian Empire, and be crowned as its emperor by the Pope on Christmas Day of 800. The era he was born into almost demanded extreme measures, as summarized by Weber in his opening narration to Episode 17, “The Dark Ages,” of The Western Tradition:

Weber: “It was a time of anarchy, of murder, arson, pillage, rape. A time when the world seemed to fall apart. Even the church depended on the barbarian tribes who ruled the West. As the barbarians were Christianized, the church became more barbarous. The Dark Ages, this time on The Western Tradition…”

To set the Frankish scene before Charlemagne stepped onto it, Weber utilized the Dark Age chronicles of 6th Century Christian bishop/historian, Gregory of Tours:

Weber: “Frankish history, or at least what we know of it from Gregory, is one long tale of arson and rape; murder and perjury; sons strangling their mothers; mothers throwing their sons down a well; people getting kicked or burned to death at a friendly banquet; wives encouraging their lovers to murder their husbands — and then in due course murdering their daughters, because they were afraid that they might tempt the lover away; incest rife, and sometimes leading to murder; servants and allies betraying or poisoning their masters and their friends.”

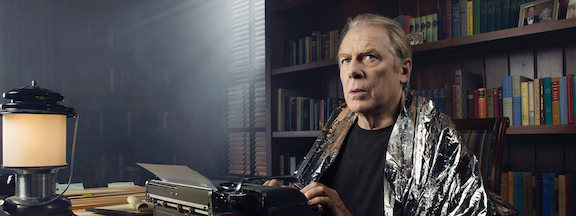

The legacy of the king/emperor which this brutal history produced was recently embodied by late film acting legend, Christopher Lee. In 2010, the then-87-year-old released his first full music album as a symphonic metal concept piece, titled Charlemagne: By the Sword and the Cross. Lee voices Charlemagne’s ghost narrating episodes of his reign on tracks like “King of the Franks,” “The Iron Crown of Lombardy,” and “The Bloody Verdict of Verden.” Lee’s heavy metal follow up album is titled Charlemagne: The Omens of Death, and includes the evocatively biographical tracks, “Massacre of the Saxons,” “Let Legend Mark Me as the King,” and “The Devil’s Advocate.”

However, rulers of Charlemagne’s caliber and vision were in short supply following his death in 814 — and the era of devastating Viking invasions left it to the leaders of smaller states to organize Europe’s defense against destruction, as Weber sums up in the closing narration to his look at the Dark Ages:

Weber: “The Count of Paris; or Rollo and his descendants in Normandy; or Henry the Duke of Saxony and his son Otto, who finally beat the Hungarians to a pulp. These new princes derived their authority from their military leadership, and from their power to protect their country. And indeed, a series of victories by the mid-900s would mark the turn of the tide. Much suffering was still in store for the West, but the worst of the horrors had passed, and the survival of Christendom was secured, as we shall see next time…”

Coming Soon, Part Two: The Archaeologist!